Eastwoods Group: 1934 Review

Note: This is a sub-section of Eastwood Group

Note: This is an abridged version of a chapter in British Commerce and Industry 1934

FEW industrial organizations have fallen in so naturally with the times as the companies now known as the Eastwoods Group. Their record has been one of timely organization and sound administration, of continuous growth and expansion, of consolidation, and consequently of steady dividend-earning success, from 1920, when the parent company of Eastwoods Limited was reconstituted after the Great War.

For the business of Eastwoods is, of course, over a century old, having been established in 1815. As a private and family concern it prospered through several generations, and was widely known — particularly in the Eastern and South-Eastern Counties of England — for its large output of stock bricks and flettons, and its facilities for the supply of all builders' materials. It owned wharves, depots and a large fleet of river barges and road transport for the purpose of its business, and these were the foundation upon which the post-war group has been built.

Consequently, in 1920, after the turmoil of war activities, as if by some stroke of business inspiration, the century-old interests of Eastwoods were transformed almost overnight on to a new plane of activity, and a public company with a capital of £300,000 was the first herald of this.

In 1925 the capital was increased to £450,000, and since that time, several further public companies have been launched, amongst them being Eastwoods Cement in the same year, and Eastwoods Flettons in 1927, each with a capital of £200,000. In addition to these there have been important acquisitions either with the view of increasing outputs and of marketing allied materials, or of making the group more self-contained, for economic service to the building and constructional industries. Amongst these have been the formation of Eastwoods Lewes Cement Limited, Eastwoods Wharfage Limited, and the Barrington Railway Co, and the acquisition of other interests which have brought the combined capital of all the interests concerned to the region of £1,200,000.

In any comparison of the condition and organization of industry in pre-war England, with the new efficiencies of the post-war period, no more characteristic illustration need be sought than in the evolution of this group.

Until 1920 Eastwoods had fulfilled an important role in the long industrial epoch which was, in any event, drawing to a close in the second decade of this century. They had followed traditional methods — the best considering the age —but the time was becoming ripe for great changes in the technique of production for all types of industrial enterprise, on account of the strides made in the engineering industries and the electrical power supply, by the use of machinery which increased the scale of outputs, speeded them up, and completely revolutionized the old internal economy of production. In both brick-making — one of the oldest of human activities — and cement-making (almost as old, from the evidence of the Pyramids), rapid evolution has amounted to a revolution. Mechanized and mass production began to supersede the older methods, and a short glimpse of some of the Eastwoods units in operation will demonstrate this.

First, brick-making. Eastwoods Limited, one of the largest stock brick-makers in the industry, have extensive brickfields in Halstow and Conyer in Kent, providing 26 millions of machine-made, kiln-burnt stock bricks per annum; Leney, Four Gun, Cloverley, Otterham, Britannia, Halstow and Teynham, also in Kent, and three fields at Shoeburyness in Essex, with a combined output of 54 millions of hand-moulded stock bricks a year; Fletton and Yaxley, near Peterborough, the original home of the fletton brick, with an output of 34 millions of flettons a year, which will be at least doubled with the extensions now in hand. The total output of bricks from the Eastwoods Works is well over two hundred millions a year. All are being absorbed by the almost voracious appetite of the building industries, and are likely to be in even greater demand during the coming years considering the developments that are being pushed forward both in the social world for essential housing, and in the business world for the modernization of works and factories.

As the Fletton brick has come to the front in recent years, its manufacture at Kempston under the up-to-the-minute methods of Eastwoods is of interest.

Fletton bricks take their name from the village of Fletton near Peterborough, and they were introduced originally several generations ago by Eastwoods, who still own the first works opened in that place. At first the building industry was hesitant in its attitude to these new products. Their comparative cheapness, which could not at first be reconciled with value and quality, was due to the elimination of a preliminary drying process, and to their oil and carbonaceous content which reduced the quantity of coal required for their burning in the kiln. Their excellence, however, established them in the building industry, so that they are to-day more popular and more universally in use than any other kind.

Their manufacture can only take place from the well-known bed of clay which extends across England from Lincolnshire to Dorsetshire, the raw material being known by the technical name of "Knotts." Although the quality of the knotts varies along the bed, as might be expected, the deposits around Peterborough and Bedford are acknowledged to be the best. Eastwoods Limited found that the capacity of their works at Fletton and Yaxley was insufficient to meet even a localized demand. Eastwoods Flettons Limited was accordingly organized and financed with the assistance of a ready public in order to supply a further output of 60 million bricks per annum from Kempston Hardwick in the neighbourhood of Bedford. This output was obtained from two sets of kilns, together with a modern power station and brick-making plant, the whole of which have since been duplicated.

Having been established as recently as 1927, Eastwoods Flettons are in possession of one of the finest brick-making plants in the country. The kilns, now four in number, are outstanding features of the local landscape, and are of the continuous type, two fires being kept travelling continuously around them at a distance of half a kiln from each other. Each kiln is 264 feet long and 125 feet broad, and over 14 million bricks have been utilized in their construction. The internal accommodation is divided into thirty chambers with a total capacity of a million and a quarter bricks. Coal for firing is conveyed by a portable elevator to the top of each kiln, but owing to the carbonaceous matter present in the knotts the bricks to a certain extent burn themselves. Loading platform and sidings are alongside all the kilns, lorries drawing up on specially constructed concrete roads and railway wagons on special sidings, with direct main line connections.

The first process in manufacture is the extraction of the knotts from the quarries. After the removal of the surface "callow," a mechanical digger scrapes the face of the knotts into a bucket, and swings the contents into a hopper for transport to the works. The digging machine resembles a crane on caterpillar wheels, and four thousand tons of knotts are removed for every one million bricks made. When these works are on full output, therefore, internal and external transport is utilized for the handling and disposal of about 20,000 tons of raw material and finished products per week. A continuous supply of raw materials is provided automatically throughout each working shift by means of the chain-haulage gear which, in conjunction with the quarry railway system, brings the works into immediate proximity with the clay-face.

Then follows the grinding and screening of the knotts, which are discharged into steel hoppers and reach the grinding pans by an automatic feed, the regrinding of the coarser particles being also automatic until they pass the fineness of the screen. The diameter of each grinding pan is 9 feet and the weight of each roller 22 tons.

On completion of this first process, the ground material drops from the screen into the boot of a bucket type elevator and is conveyed to the top of the building. Here it again meets a circular wire-mesh screen, the "fines" passing through it down a chute to a travelling steel band, and the "rejects" passing back for still further grinding. The steel band conveyer is of the endless type, 0.035 inches thick, and carries the ground knotts into a series of hoppers placed below. The material is now ready for the brick presses, each of which receives its supplies from a corresponding hopper immediately overhead.

Each moulding machine is of the repress pattern in which the brick is subjected four times to heavy pressure equivalent to 80 tons before it is delivered ready for burning in the kiln. The delivery of the "green" bricks from the presses to the kiln chambers is effected by means of specially constructed bogie trucks running on a Decauville light railway. The problem of direct handling has thus been reduced to the absolute minimum.

The whole process of manufacture on these mechanized principles has only been rendered possible by the installation of the latest power and engineering plant on a carefully planned lay-out, which permits of large-scale operations at a minimum of cost.

As with the knotts for Flettons, so with the marl for cement, Eastwoods are fortunate in their supplies of the raw material. They are in possession of two extensive properties for cement manufacture, the greater being at Barrington in Cambridgeshire, equipped with two modern rotary kilns together with all necessary cement and power plant for producing 150,000 tons of the best quality standard and rapid hardening cement per annum, and the second property being the old-established cement works at Lewes in Sussex, which is similarly equipped for an output of 40,000 tons of standard and rapid hardening cement, and 10,000 tons of lime and white chalk per annum.

There are few more up-to-date plants in the country than at the Barrington Cement Works. From its formation in 1925, the company received the unhesitating support of the public with capital, and besides commencing with almost inexhaustible supplies of first-class raw material, was fortunate in being able to retain the services of one of the most eminent firms of consulting engineers in the country to design the lay-out and plan production in accordance with up-to-date engineering practice. The company's record has accordingly been one of unqualified success, its balance sheet after only nine years being entirely restricted to tangible assets of nearly £300,000 on an issued capital of £200,000, and its record of dividends being continuous from 1928.

Barrington chalk or "clunch," as it has been called, is of historical interest. It was used in the building of the quadrangle of St. John's College, Cambridge, and its enduring qualities are proved by the local church at Barrington, which dates back to 1170 and was built entirely of this clunch. Cement has been produced on this property certainly since 1825, and the supplies of raw materials on the company's own freeholds extend over 215 acres. Plant for the manufacture of 75,000 tons per annum was at first installed, but very soon a second kiln and the necessary ancillary plant were added to double the output.

As an illustration of the thoroughness with which the engineering and management problems of manufacture have been planned, it is interesting to note that the making of cement requires an extensive supply of water, and the company has secured all its requirements in this respect by sinking an artesian well to a depth of 190 feet, which yields a continuous supply of 10,000 gallons per hour.

The manufacture of cement at Eastwoods Cement Company's works consists of four

main processes beginning with the extraction of the raw material from the earth, its washing, wet-mixing and screening into a creamy slurry, its drying, burning and calcining to a hard clinker in a tubular kiln, and finally its grinding into the fineness of cement.

The cement marl is excavated from the quarry by mechanical diggers and is delivered by chain-haulage gear and side-tipping wagons direct into the wash-mills, of which there are three, each consisting of a pit 20 feet in diameter, around which are fitted perforated steel plates through which the slurry is washed into a surrounding trough.

In the centre of the pit is a vertical steel shaft, to which are bolted compound steel girders spanning the wash-mill. At the bottom of the shaft a steel spider is fitted with specially designed harrows which, by the rotation of the vertical shaft, are dragged through the material, thus reducing it, after the addition of water, to the consistency of a thin slurry, which is beaten through the surrounding screens into the outer channel. The slurry then flows into enclosed vertical bucket elevators, which deliver it to the wet separators. Each of the three wash-mills is capable of producing twenty tons of finished slurry per hour, which gravitates to either of the two slurry storage mixers. These are each 60 feet in diameter by 12 feet deep and afford storage of about 2,100 tons of slurry equivalent to 1,000 tons of finished cement. These mixers are of the "Sun and Planet" type, and each comprises a reinforced concrete tank having a central pier on which is mounted a steel lattice girder spanning the full diameter of the tank and free to revolve on conical rollers rotating on a fixed roller path bolted to the centre pier.

Suspended from this girder are four steel stirrers, which are driven by bevel gear wheels from a horizontal shaft and electric motor mounted on the overhead platform. On revolving these stirrers in the slurry the reaction causes the main slurry girder to revolve and the whole contents are thus kept in constant agitation.

The slurry is pumped from the mixers to the kilns by three-throw plunger pumps and is conveyed into the kiln by an ingenious spoon-feeding device.

A modern cement kiln comprises a series of circular sections from 9 feet to 10 feet 6 inches in diameter riveted together to form a cylinder of steel plates 200 feet in length, which is supported on cast steel tyres carried by heavy steel rollers. The kiln is lined entirely with firebricks and is driven at a point near the middle and rotated at a speed of about one revolution per minute. The liquid, on entering the kiln, meets the hot gases of combustion and the water is extracted from the slurry, which, as it gravitates down the kiln, is gradually dried and eventually calcined in the burning zone, where a temperature of 2,500-2,800 degrees F. is produced from the combustion of pulverized coal introduced through the firing end of the kiln by specially constructed fans.

At the completion of this operation a hard clinker is formed which is then discharged into a rotary cooler and cooled by meeting the incoming air, which is passing into the kiln to maintain combustion.

The clinker is then conveyed to storage bunkers for the two cement grinding mills, each capable of an output of ten tons of finished cement per hour to the British standard specification. The highest quality rapid hardening cement is also readily obtained.

From the mills, the cement of either grade is elevated and discharged into one of a series of silos, the capacity of which exceeds 10,000 tons.

A fully-equipped laboratory acts as a constant check on the standard of the product. A correct analysis of the material is continuously maintained from the time the marl is dug in the pit until the finished cement is packed, thus ensuring a uniform high quality for every bag sold from the works.

Electric power for the works is supplied by an up-to-date power station on the premises, the boiler house containing three water tube boilers, each capable of generating superheated steam at the rate of 20,000 lbs. per hour at a steam pressure of 250 lbs. to the square inch. The boilers are fitted with mechanical stokers and automatic coaling arrangements are provided.

The engine house adjacent to the boiler house contains one turbo-alternator set of 1,500 kw. capacity, a second set of 1,000 kw. capacity, and a week-end reciprocating set of 250 kw. capacity. A special switchboard controls the machines, and also all the works feeders or cable circuits.

From the manufacturing side, therefore, Eastwoods are impressive for the business-like basis of all activity at their manufacturing centres, the efficient character of their management, the equipment employed, the engineering knowledge and skill behind all processes, superseding much that was standard practice even a few years ago, and above all, the undoubted cohesion secured between the various companies' many sided activities. In seeking an explanation for this note of detailed efficiency in all departments of the group, it is impossible not to pay a tribute to one man who may be said to combine all the foregoing attributes of the various businesses in his own personality.

It was Mr. Horace Boot, M.Inst.C.E., M.I.Mech.E., M.I.E.E., who in 1920 foresaw the new opportunity for the old-established organization of Eastwoods, and there is unanimity in the view that it has been his experience, his engineering knowledge and gift of sound commercial judgment that has built up the group to its present high position. Mr. Boot is vice-chairman and managing director of the parent company, and chairman and managing director of the associated companies. With the assistance of the firm. of consulting engineers of which he is the head, the Eastwoods interests have the benefit of the best engineering experience and practice available in the country, in regard to design and lay-out, the planning of large works with continuous outputs, and knowledge of the latest engineering appliances.

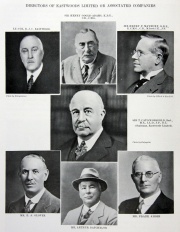

The Eastwoods group is served by a body of directors of wide experience, and extensive industrial connections. The chairman of the parent company is Sir T. Cato Worsfold, Bt., M.A., LL.D., J.P., D.L., and his colleagues (with Mr. Horace Boot as vice-chairman) Lt.-Col. R. J. C. Eastwood and Col. Sir Henry GooldAdams, K.B.E., C.B., C.M.G. In addition, the associated companies are served by Sir Henry P. Maybury, G.B.E., C.B., M.I.C.E., who has served the country with distinction in other connections, Mr. Frank Alder, Mr. Arthur Batchelor and Mr. E. A. Glover, Mr. G. W. A. Miller, F.I.S.A., the Secretary of Eastwoods, and Mr. J. T. Read, the Sales Manager.

The active management of the group is entirely under the guidance of Mr. Horace Boot. Centralized control is exercised from the original headquarters of the early Eastwoods organization on the side of the Thames at Belvedere Road, near Waterloo Station. Associated with Mr. Boot, each in his sphere, are Mr. G. W. A. Miller, F.I.S.A., as a director of Eastwoods Cement, Eastwoods Wharfage, and the Barrington Railway, and secretary of the remaining companies, and Mr. J. T. Read as a director of Eastwoods Flettons and sales manager of the group.

On this inner triumvirate rest the many responsibilities connected with the operations of the individual companies and the co-ordination of the varied interests of the group. For in addition to the enterprises already mentioned, the Eastwoods Companies comprise businesses engaged in the sale of coal, sand, ballast and the general merchanting of all builders' materials. These are conducted through subsidiary companies of Eastwoods Limited which include Hoare, Gothard and Bond, Hoare, Gothard and Bond (Dover), Ltd., W. H. Pearson, the Longside Sand and Gravel Co, and the Harold Wood Brick Co.

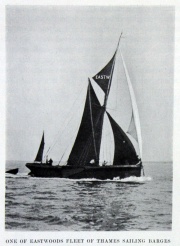

It follows that on the distributive side the interests of Eastwoods are as important as their productive activities, for the organization covers probably the most populous area in the world, from the South Midlands and Eastern Counties through London to the South-Eastern Coast towns. Within this area the group maintains over forty depots and wharves for distribution and shipping trade respectively, a large number of heavy and light motor and horse transport vehicles, and a fleet of forty sailing barges.

Taken together, therefore, these activities confer a self-contained character on the group, and a thoroughness of organization which cannot well be improved upon in the interests of the users of Eastwoods products. As a final illustration of this thoroughness of management, the construction of the Barrington Railway to serve the Cement Works at Barrington is notable. This is a standard gauge railway, one and a quarter miles long, from the main L. and N.E. Railway line at Foxton to the works. It was constituted under a special series of Light Railway Orders, and the traffic borne on it to and from the works is in excess of 75,000 tons a year.

Such, in rapid review, are some main features of the Eastwoods enterprises; unlike so many industrial undertakings in the country, they have been organized with sound financial as well as technical shrewdness, and their returns to their five thousand shareholders have been eminently satisfactory in spite of the trying and uncertain conditions which the building industry has experienced since 1920.

Dealing with some of these, Mr. Horace Boot in his address in 1933 stated: "It should be borne in mind that although Government assistance has been given to local authorities, public and private builders, and to all sorts of housing associations and various societies, at no stage has the Government ever spent one single penny in subsidizing or helping the brick and cement maker. Consequently we have been at the mercy of the changing policies of Governments and of the altered financial, social and economic conditions during that period. At no time during the past ten years have the brick manufacturers ever been given a comprehensive forward programme of building and slum clearance for the masses. If they had, there would have been sufficient security to attract all the necessary finance into the industry for the purpose of constructing new works in this country and expanding the production so as to exclude foreign bricks entirely. There was no shortage of bricks when the embargo was put into effect last autumn. Foreign bricks had been practically excluded by the ability of the home manufacturer to meet all demands. Prices were reduced in all grades, and it was necessary for manufacturers carrying stocks to realize them at a considerable sacrifice. The Eastwoods group actually made and sold more bricks than during the previous year. On the sudden removal of the embargo an enormous demand arose with the return of confidence in financial circles. The usual seasonal increases were also due, with the result that common bricks could not be supplied fast enough. They were, however, demanded at the already debased prices then ruling in quantities which obviously could not be supplied at once. In normal circumstances, orders would be placed for a few schemes at a time. References in the press, however, have been made to contracts for ten and twenty millions which could not be fulfilled and which, therefore, it is suggested were placed abroad at higher prices. Twenty million bricks weigh nearly 60,000 tons, and would be sufficient for the erection of about 1,000 houses. Deliveries of those quantities in the most favourable circumstances would be required over a period of several months. I mention this to indicate the harm which arises from a campaign of that kind, and the unfairness of conclusions hastily drawn from inaccurate information. In many of the works, notably the stock brickfields, the production programme has to be planned a whole season ahead, and even at the Fletton works, where production is continuous, a delay of several months is necessary before the works can be restored to maximum output.

"I want, however, to emphasize the fact that prices have not been increased, and during the present demand for common bricks the foreigner has again been able to come in, in large quantities, notwithstanding the 10 per cent. tariff and rate of exchange. This is rendered possible by the low freightage rates earned by the foreign vessels which handle this traffic, and to the difference in the levels ruling on the Continent in such matters as wages, the standard of living, taxation and social services. Under these conditions it is the foreigners' surplus production which is dumped here and which results in the transfer abroad of funds which ought properly to be financing industry and the employment of labour in this country. These imports, particularly in the Thames and East and South Coast areas, have definitely debased prices and wages and caused the stoppage of many of the smaller works during the critical period of the last year. I regret the Tariff Committee still encourage the import of foreign bricks, inasmuch as they have refused to grant more than 10 per cent. duty, although it was pointed out to them that the British worker took 80 per cent. in wages of the cost of brick production, that about 21- million tons of coal were used annually in the industry, and that all the raw materials used were found at home. There was therefore a strong reason for prohibiting the import of foreign bricks, or at any rate for imposing a heavier duty."

In the light of the foregoing it is interesting to note that the Government in the autumn of 1933 launched their National Slum Clearance Scheme, which was readily sponsored by local authorities throughout the country, and has since been widely taken up by the London County Council and other important bodies.

Despite these conditions, however, the Eastwoods group has been well managed, and is occupied to its present capacity. The real handicap under which it suffers is the fact that the commercial demand for its products prevents any considerable part of its current make being devoted to a construction programme within the industry with a view to increasing outputs still further. At present, bricks for the latter purpose are only obtainable at the expense of foregoing current demand. The present demand in England is undoubted for many years to come, and the capacity of existing producers is insufficient to meet it. It should therefore be made possible for a singularly successful group to enlarge its capacity to meet the requirements of building and construction works inside the country, which have been conservatively estimated at more than 5,000 million bricks a year.

Both bricks and cement are the capital goods of other industries, and their manufacture, in addition to ranking as a primary industry, is at the root of the general industrial efficiency of the country, and of the amenities of social life.

This country has long enjoyed a reputation as the producer of the finest bricks of all types in the world. New types are being continually evolved through successful experiments and the surmounting of difficulties by chemists and technical workers. The Fletton brick itself is being transformed by Eastwoods into a medium priced facing brick, which has already received the warm approval of leading architects. This improvement has been secured by means of machines acquired by the group on monopoly terms, for the treatment of Flettons by a mechanized process. A complete manufacturing unit is already in operation and is meeting with a rapidly increasing demand for the new product. There is therefore no marking time in the progress of the companies under Mr. Horace Boot's control.