Robert Wigram Crawford: 1886 East Indian Railway

Note: This is a sub-section of Robert Wigram Crawford and the East Indian Railway

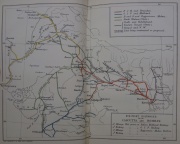

IN the course of two or three years from this time certain events will have come to pass in India, each of them of sufficient importance in itself to affect materially the working of the Main line of the Undertaking of the East Indian Railway, and taken together, if judiciously administered, to determine the conditions of the final development of what may appropriately bear the name of the "Ganges Valley System" of Indian Railways.

These events, taking them in the order of the dates of their probable accomplishment, are,

- (1) The completion of the bridge crossing the Hughli river, near the town of that name, twenty miles above Calcutta.

- (2) The completion of the bridge crossing the Ganges river at the City of Benares.

- (3) The power of the Secretary of State to acquire the undertaking and property of the Oudh and Rohilkund Railway Company in 1887.

The development of the Bengal and North-Western lines, serving, with the Tirhoot State line, the important provinces north of the Ganges, watered by its affluents the Gunduck, Raptee, and Gogra rivers, contributes also to the same ends.

In considering the general effect of the accomplishment of these coming events, I shall be excused, I hope, if I refer to my evidence as a witness before the Select Committee of the House of Commons on "East Indian Communications" in 1884, and to the opinions I then expressed upon the main features, and some of the details, of the case, differing, though they happen to do, very materially from the views of most of the other witnesses.

Question 3660. I stated at the onset that I held the demand of the commercial public, in this country and in India, for an annual outlay of £20,000,000 sterling for ten successive years to be much exaggerated. I stated that it was founded on a mistaken view of concurring circumstances, namely, an exuberant production, and low rates of freight and exchange, to and with this country, which might not recur, and in fact have not since concurred again, and which had led to so large an export of grain, seeds, and other commodities in 1883.

Those opinions I retain in full force.

Question 3662/3. I set it down also as lying at the root of the proposal to expend vast sums of money on the extension of Railways in India, that the natural configuration and geographical features of the country should be examined and correctly understood in the first instance, pointing out that, whilst so far as the provinces for whose productions it was desired to obtain more free and cheaper access to the sea, were many in number and extended over a vast expanse of territory, two Ports only had been provided by nature, those of Calcutta and Bombay, (Kurrachee is an artificial port altogether, the creation of the last few years) by which the productions of India could find their way to Europe, etc.. As these ports cannot be increased in number, for any useful purpose, by the mind or hand of man, and as they are both of them already furnished with sufficient first-class railways communicating with the interior of the country, I held that the real policy of the day was to be found not in additions to the number of existing lines communicating with the sea, but in improvements and enlargements of the existing trunk lines. The concession of the scheme for the Indian Midland Railway of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway Company, from Bhopal through Jhansi to Cawnpore, accords with that principle, though the line may be found not to answer altogether the expectations of its promoters, for reasons which I ventured to submit very fully to the Committee, and will refer to again here and so are the bridges and other works in the, and near the, Ganges Valley, already referred to.

For the purposes of these remarks, the Railways of Gangetic India may be held to constitute the following systems

- The Ganges Valley System, served by the East Indian line and branches, and the narrow gauge lines of the Bengal and North-Western, extending far to the North and North-West.

- The Oudh and Rohilkund provinces served by the Oudh and Rohilkund System.

- The Upper Doab, independently of the East Indian line, as far as Delhi, served by the Bombay, Baroda, and Central India, as incorporated for working purposes with the Rajpootana lines.

- The provinces Northward of Delhi by the North-Western State Railway and affiliated systems.

Omitting from present consideration the last of these systems, with its own separate port of Kurrachee, there remain the Great Indian Peninsula, and Bombay and Baroda, and Rajpootana systems, contending, each of them with the East Indian Railway, for the traffic of the Gangetic region, over the whole of the upper part of its system, and together, with the prospect of severe warfare in the future, for such part of that traffic as they may be able to abstract from the East Indian. The terms and conditions on which these battles will be fought will be examined later on. In the meantime, the chief determining factor in the contention is the competition of the rival ports of Calcutta and Bombay, for the traffic of North-Western and Upper India.

This competition was unknown, in point of fact it was not possible, before the meeting of the East Indian and Great Indian Peninsula lines of Railway at Jubbulpore in the year 1869, and it has been effective only since the completion of the Rajpootana-Malwa (narrow gauge lines) and their incorporation with the Bombay and Baroda line in 1884, thus affording Bombay a continuous unbroken communication with points of contact with the East Indian line at Agra and at Delhi. The basis upon which this competition is, as regards Bombay, the great superiority the port possesses over the port of Calcutta, owing mainly to natural causes - the extent and depth of the water of its harbour, its facility of access and immunity from cyclones, and, more than all, its position, confronting, on the Western Coast of India, the entrance to the Red Sea, and the communications with every part of Europe. Add to these the moderate port charges, and there appears to be some reason why there should be a reputed difference of 10s. per ton in favour of Bombay between the freights from Bombay and those from Calcutta, and just so much, say 10s. per ton, in the relative costs of the transport of goods between the marts in Upper India and the destination in Europe.

If by the gifts of nature Bombay is so largely superior to Calcutta as a shipping port, there is a set-off of no slight importance in the fact that the approach to, and departure from, Bombay, are subject to the drawback of the Western Ghats in both the lines of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway leading into the interior of the country, and the flooding of the rivers, notably the Taptee and Nerbudda, which cross the path of the Bombay and Baroda Railway in its northward course to its junction with the Rajpootana-Malwa line at Sabarmati (Ahmedabad). Added to this, coal is not to be found economically suitable for the purposes of locomotion at any point of either of these lines. The con- sequence of this is that both of these depend upon the imported coal into Bombay for the supply of their requirements, at a cost as follows, as compared with the East Indian Railway Company for the last three half-years of which we have the account before us. Thus the

[See table of data on image]

or in other words showing that the East Indian Railway would have had to pay Rs. 11,26,398, Rs. 8,71,310, and Rs. 10,05,405 more in each half-year towards the working expenses, if the cost of her coal had been as high as that used on the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, and the Great Indian Peninsula Railway would have paid Rs. 11,08,100, Rs. 7,48,282, and Rs. 10,88,642 towards the working expenses of the same half-years, if the cost of her coal had been as low as that used on the East Indian Railway.

It was with a full view of all the possible changes in the future in connection with the competition with Bombay, that the Directors of the East Indian Railway entered upon their labours under the new regime in 1880. The advantages of the port of Bombay as compared with Calcutta were indisputable, and it soon became apparent to them that if Bombay did really possess a superiority, measured roughly by the sum of 10s. per ton in her favour in her homeward rates of freight, (The reputed difference of 10s. a ton is used for the sake of argument; but this difference is not confirmed by the published tonnage schedules of the two Ports. They differ much from each other in what constitutes a "ton.") it behoved them to avail themselves of their own great advantages, in the matter of gradients and cost of coal, to place themselves on, or as near as could be made, an equality with Bombay in the matter, by the observance of every practicable economy in management, the supply of engines and waggon stock of the most approved power and capacity, and the utilisation, to the utmost, of the space at their disposal at Howrah, so as to afford every facility and, as far as possible, remove every disability under which the free conveyance of goods from the North-West and their shipment at, or distribution in, Calcutta, could be said to labour.

In the carrying out of these ends, the building of the great bridge to cross the Hughli, near the town of that name, with the view of relieving the congestion of goods at Howrah, was the measure first entered upon. The enlargement of the station works at Howrah was next proceeded with. As many as 209 new locomotives of the patterns best adapted for a heavy traffic have been supplied or are under contract, whilst 2,000 goods waggons of large capacity have been constructed and sent out in the last ten years from this country. With these and other provisions in hand the Board are prepared to enter into a free and open competition with the Great Indian Peninsula Railway and the Bombay and Baroda Railway for the traffic of the North-West, confident of being able to hold their own, if they are only allowed fair play.

The following statements will show the grounds on which the Directors of the East Indian Railway Company base their hopes in the coming contest. Taking the Great Indian Peninsula Company first, whose avowed object in getting to Cawnpore is to divert from the East Indian Railway and to gain for themselves, by the establishment of the "Midland Railway," so much as they can, if they can, of the traffic from Cawnpore to Calcutta, we find the following facts bearing so considerably on the issue, as to leave but little doubt as to what that issue will be.

Cawnpore is distant from Calcutta 684 miles, and it will be, it is understood, 831 miles distant from Bombay. Consequently the distance from Bombay to Calcutta by the two routes conjointly being 1,515 miles, the half-way house or mid-point of the entire route will be at 757 miles from either port, or about 31 miles distant westward of Calpee. In other words, "all things being equal," a ton of goods could be sent from that half-way house to either port for the same charge for freight.

But all things are not equal in this case of competition. If, on the one hand, the Western Port of India is unsupplied by nature with coal of any kind for the locomotive uses of the Railways, and the courses of those Railways are impeded and obstructed by mountain ranges and the opposing waters of great rivers, we find, on the other hand, Calcutta in immediate connection with coal-fields of great extent on the very line of her chief Railway, and that Railway (the East Indian) pursuing its way of nearly 1,000 miles to Delhi over a course practically level throughout.

The results of these differences in the natural conditions under which the East Indian and the lines of Western India are worked have been formulated in the "Summary of Analyses of Working" appended to Colonel Stanton's Report of the working of Indian Railways for the half-year ended 31st December, 1884. In that report appear the following figures:-

Average cost of hauling a Goods unit (viz., one ton) one mile.

- EAST INDIAN .RAILWAY pies 2’40 at 1s. 8d. '25d. per ton

- GREAT INDIAN PENINSULA RAILWAY pies 5’27 at 1s. 8d. '55d. per ton

- BOMBAY AND BARODA RAILWAY pies 4'77 at 1s. 8d. '49d. per ton

- RAJPOOTANA RAILWAY pies 5’20 at 1s. 8d. '54d. per ton

A difference in the working capacity of the East Indian and Great Indian Peninsula lines, respectively, sufficient to transfer the central economical working meeting point on the Indian Midland line, 356 miles to the westward of Cawnpore.

It is true that no practical result can ensue from this state of things, as the Midland will be in the hands of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway Company, but the facts remain as I have stated them, and justify the conclusion I have come to, that the East Indian possesses, in the cheapness of its working under the circumstances I have named, a compensation for those advantages which nature has so liberally bestowed upon the Port of Bombay.

In the case of the competition with the united Bombay and Baroda and Rajpootana-Malwa lines to Agra and to Delhi, the case is somewhat different, the distance from Calcutta to Agra being 841 miles, and from Bombay to Agra 848 miles, the midway house is 3.5 miles to the west of Agra, or, as nearly as may be at Agra itself, but the economical working midway point would be at 307 miles to the westward of Agra; a matter of no account however because of the difference of gauge and the fact of the lines being in the hands of two distinct antagonistic powers.

I do not pursue the matter further as regards Delhi, because that station is, relatively to the East Indian much nearer to Bombay from a mileage point of view, but there is evidence of our power to compete with the Rajpootana Company in the fact that we find in recent correspondence, our East Indian Traffic people asserting their ability to lower their through rates from Delhi to Howrah for whole trains of wheat and seeds, from Rs. 16.5.0 per ton, the rate current for some time, to Rs. 12; the Rajpootana rate being Rs. 18 to Bombay. The last locomotives sent out by the Board, expressly for the purposes of meeting Western competition, are stated to be equal to draw 800 train tons over the easy gradients of the line.

The Hughli Bridge will be completed, it is hoped, and opened for traffic early in the year 1887, and will at once remove any cause for apprehension of a renewal of the congestion of goods in the Howrah station, such as took place in 1883, provided that steps be taken sufficiently early by the Local Government to provide fitting access from the bridge end on the eastern bank of the river to Calcutta - a distance of 20 miles - and adequate reception to the goods so carried. The Board have no ambitious views of a Central station in the City, or future connection with the proposed Kidderpore Docks or works at Diamond Harbour to concern themselves about. They ask the Government for such accommodation only on the eastern side of the river, as may give full effect to the objects for which the bridge has been constructed.

At the present day, when 1s. in 33s. per quarter in the price of wheat means a profit of about 3 per cent., a profit for which people are content to work, as the saying is, it is manifest that however small may be the margins within which reductions of charge or compensations can be sought for, none are too small to be neglected in the effort to reduce to the utmost possible extent the cost of carriage (including charge of every kind) between the places of production in the interior and shipment at Calcutta.

With these views before them, and looking always to the policy of removing all obstructions from the free course of traffic on their line, reducing charge of every kind where reduction was possible, and providing at any reasonable cost locomotive power and waggon stock of the most approved descriptions, the Board could not welcome the design for the docks proposed to be built at Kidderpore, and which it is now stated are being proceeded with at an estimated cost of £3,000,000. I do not intend now to argue the pros and cons of this much debated scheme, but it does appear to me to require more substantial reasons to be given for so questionable an expenditure, involving, if estimates be not exceeded, and the work be successfully completed, an annual charge of, more or less, £150,000 upon the trade of the port, at a time when so much has been done and. remains to be done in the way of relief in other quarters. (At the close of November, the Port of Calcutta accommodated 88 vessels of all sorts, up to steamers of the largest class, at the Jetties of the Port Commissioners, and moorings in the river)

The following is from a recent publication at Bombay bearing on the subject:-

"The new docks question still continues to exercise public attention, with the fear that the scheme may yet be carried out, and a further needless addition made to port charges on shipping, which are already higher than in any port in the world probably. In the opinion of those who have watched the trade of Calcutta for years, and the intercepting influence of the natural advantages of Bombay as an outlet to Western nations, the falling off in the totals of the trade of Bengal already registered is but a prelude to a more marked decrease. To remove rather than add to the burdens on the trade of the port, in unnecessary directions, should be the aim."

The completion and opening of the bridge of the Oudh and Rohilkund Railway Company at Benares (which it is said may be expected to take place at the same time as the opening of the Hughli Bridge), will undoubtedly affect very largely the development of the Oudh and Rohilkund system, by bringing the whole of that system into direct communication with the East Indian Railway at Moghal Serai. The distance from Moghal Serai to Cawnpore by the East Indian line being 215 miles, and 248 miles by Fyzabad and Lucknow, it follows that the mean distance is 291 miles to the westward of Lucknow, and miles to the eastward of Cawnpore, and that, consequently, there need be no apprehension of the Cawnpore traffic being transferred from the East Indian to the Oudh and Rohilkund system, at the same time that the Oudh and Rohilkund districts between Lucknow and Chandausi will gain the benefit of uninterrupted communication without break of gauge with the bridge at Benares.

It is difficult to imagine that the addition of traffic thus coming upon the East Indian line at Moghal Serai, concurrent with the normal expansion of the local traffic of the country, and followed as it will be by the mass of traffic brought to the East Indian Railway at Digha Ghat (Patna) by the trains of the Bengal and North-Western line, and the Tirhoot (State) line at Mokamah, will not bring to bear an accumulation of traffic upon the East Indian line which will tax all its powers and capabilities, and that in the course of years provision will have to be made to enlarge them. It was from this point of view that I took upon myself to propose to the Select Committee the revival, by way of addition and complement to the existing East Indian system, of the plan as originally designed of carrying the main communication between Calcutta and the North-West Provinces in a line running nearly straight from Barrakur (142.5 miles) to Moghal Serai (469.25 miles). The line was fully surveyed at the time – 1850 - by competent engineers, and the details were so far worked out as to form the basis of a provisional contract, but the Government of the day very wisely came to a different conclusion, and preferred the circuitous line with its great cities on the banks of the Ganges.

The detailed levels taken in 1850 remain in the possession of the Board. They show a line practically free from engineering works of any difficulty or importance, after taking account of the descent from the summit of the Doomrah range of hills to Sherghotty, and the bridge which would be needed for the crossing of the River Soane. The length of the line would be about 260 miles, about 145 miles from Barrakur to Sherghotty, and 115 miles from Sherghotty to Moghal Serai (Benares).

The advantages of such a line, independently of its relief to the Main line, would be manifold. It would shorten the journey distance from Calcutta to Moghal Serai, and every place to the northward and westward of that capital junction by 67 miles. Following the course of the Barrakur river it would pass very near to the Kurhurbaree coal-fields, and shorten the route for coal to the North-West by 92 miles, equal, at one-eighth of a pie per maund per mile, to 2s. 8.5d. per ton. It would reduce the cost of transport by 67 miles, on all goods from all stations in the North-West to Calcutta. By a short connection between Gya and Sherghotty it would give an alternative route of 364 miles between Patna and Calcutta by, way of Sherghotty, instead of 338 miles by the direct line, and to the extent of an additional run of 26 miles render Patna and its connected stations, independent of any mischief that may happen on the exposed parts of the line about Luckieserai. It would also relieve the traffic of the North-West Provinces from the consequence of any accident that might happen to the Soane bridge. In a word, the construction of this GRAND CHORD LINE, as it may be termed, between Barrakur and Moghal Serai would consolidate the great railway system of the Gangetic Valley; retaining its own arterial traffic it would receive and facilitate the distribution of the traffic of its tributaries.

My object in preparing this paper has been to show how little there is to apprehend in the interests of the holders of the Deferred Annuity Capital from the rivalry of the Western lines connected with Bombay. There is room for us all, and for each Company to attend to and manage its own affairs without heat or temper.

R. W. CRAWFORD.

5th January, 1886.

See Also

Sources of Information