Autobiography of Richard Tangye: Chapter 12

See Richard Tangye

CHAPTER XII. "UNION IS STRENGTH" — CONCLUSION.

FOR more than a century past there has been an intimate connection between Birmingham and Cornwall; for Boulton and Watt found the best field for their pumping engines in the Cornish Mines, and were long represented there by their ablest lieutenant — William Murdock. Since that time the Cornish colony in Birmingham and its vicinity has largely increased in numbers; and during the present year an Association has been formed having for its object the promotion of social intercourse amongst them. At the first meeting of the Association I was appointed President, and acted in that capacity at the inaugural dinner. In the course of my address on that occasion, I remarked that "I had been instrumental in bringing more Cornishmen into Birmingham than any other man, and I was proud to be able to say that with scarcely an exception they had been a credit to their county.

"But in the early days of the Cornwall Works some of the Birmingham men did not appreciate the introduction of the west countrymen. One dark night I was walking home behind two of our workmen, when I heard one of them say to his companion, 'Another Cornishman come to the land of Goshen.' Well, I was glad there was a land of Goshen for my fellow Cornishmen to come to, for employment had become increasingly scarce in the old county, and many had been dispersed over the face of the globe. But wherever Cornishmen were found, their hearts always beat fondly for their dear native county, and they never ceased to cherish the hope that they would one day return to its rockbound shores."

For many years past, Cornish mining has been in a greatly depressed condition, and, thousands of miners have left to seek their fortunes in foreign and colonial lands; but concurrently with this exodus, large numbers of successful emigrants have returned, " bringing their sheaves with them," and have settled down to spend the evening of their lives amidst the scenes of their youth.

Of late years I have been relieved to a great extent from the necessity of attending to business, and have thus been enabled to satisfy a long-cherished desire to return to my native county, having purchased the beautifully situated residence "Glendorgal," on the Atlantic seaboard, and, with it, that portion of the coast which includes Trevelga Island, with its old-world fortifications, and the far-famed St. Columb Caverns. The coast scenery in the neighbourhood is amongst the grandest and most varied to be found in the British Islands; while the sands are firm, and at low water can be traversed for miles. The caverns were well described in Good Words by Dean Alford some years ago; and in the principal one, the Banqueting Hall, Clara Novello once sang to a select and enraptured audience.

This cavern is of immense proportions, and has splendid acoustic properties, and being easily accessible is visited by large numbers of people. Adjoining is the Cathedral Cavern, the roof of which is supported by magnificent natural columns of various coloured stones; while beyond is the beautiful Fern Cavern, the roof of which is covered with the Asplenium Marinum, the fronds being kept in a state of perpetual youth by the abundant supply of fresh water percolating through the strata.

My brother James, when a boy, used often to look through the garden gate of a pretty cottage near the village in which we were born; and while greatly admiring it, would think how happy the possessor of such a home must be. When, therefore, he was about to retire from business, happening to hear that the place was for sale, he eagerly bought it, and has been happy enough, during many years' possession, to realise all the dreams of his boyhood. But, like James Nasmyth, my brother quickly found he could not be idle; so being fond of the study of astronomy, he set up an equatorial telescope; and having no family to engage his attention, he has trained many a poor boy to be a good mechanic in the beautiful little workshop standing amongst the flowers in his garden.

My brother Joseph on retiring from business went to reside at Bewdley, and, like James, he soon fitted up a workshop in which he spends much of his time in making mechanical experiments and models. For some years past he has been an Alderman of the town, his practical knowledge of mechanics enabling him to render good service in the Water and Gas departments of the Corporation, and also in directing the operations of the Mechanics' Institute, in which he takes great interest,

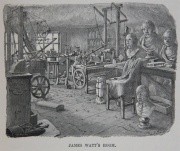

A few years since, my brother George went to reside at Heathfield Hall, near Birmingham, "where," writes Mr. Saml Timmins, F.S.A., "one of the most remarkable and interesting relics of the great inventor of the steam engine has been reverently preserved, exactly as it was left by its owner nearly seventy years ago. It is a low-ceiled room over the kitchen of the house, and with the window overlooking the stable yard. It is reached by a narrow staircase, and it is practically separate from the rest of the house. It is known as the classic garret or attic, or private workshop of James Watt, in which his later years of leisure were passed in various mechanical experiments as 'amusements' of his old age. It is now a 'relic room' of the machinery, apparatus, tools, and products of the old engineer after his fame and fortune had been made. On the left of the illustration a series of drawers is shown, in which numerous and various tools were methodically arranged; also a stove with coal-scuttle and fire-irons; and a Dutch-oven in which he could cook his own meals without being disturbed is seen over the stove. Under the window stands his lathe, with its lamp and tools left untouched as he himself placed them, and with the stool on which he sat. His old leathern apron remains as he left it. Round the walls are shelves containing fossils, minerals, gallipots, bottles, crucibles, and many small drawers carefully labelled, in which are lenses, scales, mathematical instruments, sketch books, pocket books, and countless memorials of his long and busy life. On the right hand are busts and figures, his old chair, a bench on which he many varied tools, and underneath a sad memorial, an old hair trunk, in which the school books and sketches and copy books of the early childhood of his brilliant son Gregory were kept for long years after his lamented death by his mourning father. Among other relics are those of the early machine, now universally used for copying letters, with packets of the powder sold by James Watt and Co.' to make the necessary ink for securing the copy on the damped paper.

"The two most prominent objects in the centre and on the left require more detailed description. The one in the centre is the first 'medallion,' or 'copying machine,' which Watt invented, on the principle of the pantograph, now popularly known for copying drawings, by means of a pointer at one end of a bar and a pencil at the other, the copy being larger or smaller than the original according to the relative length of the parts of the bar from the fulcrum. Watt's invention added a cutting tool, rotated by a simple action, which, in his own words, 'ate its way' into the material to be carved exactly as the other end of the bar (or pointer) was raised or lowered. A perfect copy of any medal or disc was thus secured, and many very beautiful examples remain, carved in wood, ivory, plaster, or metal. The other and more complex machine (on the left) was a further development of the ingenious process, and was devised to make complete copies of busts or figures. This was accomplished by placing the original in a sort of lathe, in which it was rotated slowly, and the pointer, travelling over its revolving cutter, thus produced an exact copy, but generally on a smaller scale. The finest examples were those of the bust of Watt, by Chantrey, most beautiful and delicate copies of which Watt gave to his friends as the 'works of a young artist in his eighty- first year.'

"The machinery was slowly improved from the 'medallion' of 1810 (his seventy-sixth year), to his death in 1819, when the bust carving machine had been perfected to reproduce copies in wood, ivory, jet, alabaster, and metals of various kinds. Some of the finest examples were those of Locke (a large example in ivory), of De Luc, of Dr. Black, and of Dr. Priestley. Although only an amusement 'for mind and body,' the same arrangements have in later years been largely used for automatic copying of 'models' or 'patterns,' such as complete gunstocks, in which every detail is produced by machinery only, without any touch from a workman's hand.

"The 'classic garret' contains innumerable examples of the inventions and productions of James Watt, from his earliest to his latest days, and even the books and papers of his father, as well as many of his own. Its interest is unique, its relics are priceless as personal memorials; and to enter the room and look around is to stand in the presence of genius at work, although the busy brain and skilful hand have been at rest for nearly seventy years."

Birmingham has long been famous for the energy and enthusiasm with which it has championed every movement for the political enfranchisement of the people, and for their intellectual and moral improvement. Public meetings on behalf of these objects have always had a strong attraction for me, and I have been present at many memorable gatherings in the noble Town Hall. One of the first meetings I attended was called by the great philanthropist, the late Joseph Sturge, for the purpose of endeavouring to calm the passions of the people while the war with Russia was raging. Mr. Sturge, in vigorous and impassioned language, pictured the misery that was being caused by the war, and denounced those responsible for it; and then, uplifting both arms, and throwing back his noble head, looking like a prophet of old, he said, "I have an only son, whom I dearly love, but I would rather follow him to his grave tomorrow than he should have anything to do with this accursed thing." It is pleasant to know that this son worthily follows in the footsteps of his revered father.

On another occasion I was present when the late David Urquhart, at one time Under Secretary for War in Lord Palmerston's administration, was denouncing that statesman with great vehemence, and demonstrating (to his own satisfaction) that he was a traitor to his country; and when, while he was in the midst of an unusually strong sentence, the deep voice of a well-known local politician interrupted him with "No! No!" Mr. Urquhart turned round, and looking at his interrupter, said in deep, measured tones, "From what Trophonean cave proceeds that horrid sound!" and then continued amidst roars of laughter.

The first time that I heard John Bright speak was while he was member for Manchester. He came to Birmingham to endeavour to rouse public opinion against the renewal of the East India Company's Charter. Mr. Bright described the constitution of the Council that ruled the Great Indian Empire from their easy chairs in Leadenhall Street, and said that "if you closed Temple Bar, and took the first hundred people who passed through it when it was opened again you would get just as good a council."

In after years it was with great delight that I took some small part in every election in which Mr. Bright was returned for Birmingham, except the last, when I was homeward bound from Australia. Happening to mention to a fellow-traveller in the train from San Francisco, that I was from Birmingham, an American gentleman sitting on the other side of the carriage, came across, and with considerable warmth said, "I must shake hands with a person hailing from the city that sends John Bright to Parliament." This gentleman told me he was a farmer in Oregon, and that a neighbour of his received the Birmingham Weekly Post. His neighbour, he said, lived fifty or sixty miles from him; but he was the nearest he had, and so he occasionally rode across to borrow the paper.

During 1879 my eldest daughter was at school at Weston-super-Mare. Inheriting strong Radical opinions, she was greatly exercised at the pronounced Conservatism of some of her youthful school companions, who, attracted by her earnestness, were not behindhand in exhibiting their "principles." They declared that Mr. Disraeli was very much better than John Bright; while she indignantly protested that it was sufficient for any one to compare their faces to enable them to come to a conclusion on that point. Things at length came to a crisis, and my daughter could bear it no longer; so without consulting any one, she wrote a letter to John Bright, setting forth her grievances, and telling him there were Tory girls in the school who spoke very disrespectfully of him, and saying, too, that her father had told her what great things he (Mr. Bright) had done for the people of England, adding, that "now she was able to judge for herself, for she had heard him (Mr. Bright) speak twice in the Birmingham Town Hall!" My daughter never imagined for a moment that Mr. Bright might have too many important engagements to permit of his replying to a school-girl's letter, but in due time her faith was rewarded by receiving the following reply:—

132, Piccadilly, London,

17th July, 1879.

My dear Mabel,

< May I thus address you, though I do not know you, and have never seen you? I am very much amused at your pleasant and interesting letter, which I have read over several times; and I can, in some degree, imagine the enthusiasm and the daring which led you, or induced you, to write it. You think I have endeavoured to do some good things in my public life which have been useful for our people, and especially for the poor among them, and your sympathy for them has made you think kindly of me. I like to think of this, and to think that many who are strangers to me, and whom I have never seen, and perhaps may never see, can approve of some things I have wished to do, or have done. I am glad you liked the great meeting at Birmingham. I hope it was useful to many there, and to some who were not there. If our people knew more of what is good for them, they might be much happier than they are — they would have more comfortable homes, and they would be able to secure for themselves a better Government — we should have less of war, and ignorance, and poverty, and crime.

I have always wished for this, and have spoken earnestly for it. When you grow up, and have more influence than you have now, I hope it will always be used in favour of justice, and mercy, and goodness; and now, even amongst your schoolfellows; you can do some good if you wish to do it, which I do not for a moment doubt.

If your papa has said to you, or in your hearing, anything kind of me, I ought to be grateful to him, and to thank him. It is something to be valued, that good and useful men can judge me kindly. I am not quite sure that he will not rather wonder that you should write to me, a stranger to you! I have written you rather a long letter in reply, and must conclude now by thanking you for your kind note; and by hoping that your holidays will be happy, and that in your school studies you may be successful. Some time when I see you, we may talk about our correspondence, and, perhaps, laugh at it. In the meantime, I am very sincerely, your friend,

JOHN BRIGHT.

In reading this letter one hardly knows which is most apparent, the goodness of heart which prompted the busy statesman to take notice of a little schoolgirl, whom he had never seen, or the great skill with which he brings the most important questions within the comprehension of one so young.

In 1879, I made my first appearance on the platform of the Birmingham Town Hall in seconding a vote of confidence in Mr. Bright and his colleagues; and subsequently I performed the same duty before an audience of twenty thousand persons in Bingley Hall. In 1881 Mr. Bright did me the honour of accepting my hospitality at Gilbertstone; and while in my library, happening to take up a copy of Forster's "Arrest of the Five Members," jocularly remarked that another edition would soon have to be written to chronicle Forster's "Arrest of the Thirty-five Members," alluding to the number of Irish members who followed Mr. Parnell during Mr. W. E. Forster's tenure of office as Irish Secretary.

For some years after Mr. Bright was first returned for Birmingham he was usually the guest of Joseph Sturge or his brother Charles, and, naturally, he saw much of the members of the Society of Friends during his visits. But upon the death of Mr. Sturge, Mr. Bright became the guest of gentlemen not connected with the Society, and in consequence its members saw little of him in a social capacity. Accordingly, when the right honourable gentleman visited me, I took the opportunity of inviting about 300 of the Friends to meet him, and the re-union was greatly appreciated by them. On leaving my house, Mr. Bright took my youngest boy by both hands, saying a few pleasant words to him and then, observing a pretty little Italian greyhound near, he said, "I see you have a little dog. I have a little dog too, and he sleeps in my bedroom!" The little four-year-old boy looked up in the old man's face, and said, "But little dogs have fleas!" greatly to Mr. Bright's amusement.

During the last few years of Mr. Bright's life many of his staunchest friends and supporters, who stood by him in the evil days when Tories and Whigs denounced him as a traitor to his Queen and country, have, to their great grief, been unable to follow him upon one great question. But happily in my own case, to quote from a recent number of the British Workman, my "personal relations with the great Tribune have not been marred by political differences. The 'empty chair' with its solitary watcher — the faithful Skye terrier looking for its lost master in sorrowful bewilderment — forming the frontispiece of the Illustrated London News of April 6th, was Mr. Tangye's gift to Mr. Bright, and one of the last messages sent from his death-bed was one of grateful thanks to him for many acts of unaffected kindness."

Of Mr. Bright it may well be said in the words of the poet- "Age sat with decent grace upon his visage, And worthily became his silver locks."

Each succeeding year that we were associated together in business exemplified the truth of the motto that "Union is strength." A better illustration could not be found of that passage of Scripture where it is said, "The eye cannot say unto the hand, I have no need of thee; nor the head to the feet, I have no need of you." The previous career of each brother was peculiarly adapted to fit him for the position he afterwards held in the management of the concern. Some were ingenious mechanics, capable designers of new machinery, and first class workmen, accustomed to the management of men; another had had large experience of the manufacturing cost department, the buying of materials, keeping of workmen's accounts, and paying of wages; while yet another had charge of the commercial department. And then, until our business was firmly established, we all lived together, and the evenings were mainly devoted to discussing the proceedings of the day and planning the work for the morrow. Some of my brothers' best inventions were made and elaborated after the day's work was over, everyone contributing his quota of suggestion, except myself, for I was the only non-mechanical member of the family. I have often thought that if at this critical period of our lives we had not been "abstainers," a different history of our future career would have had to be recorded, if indeed it had been worthy of record. I have sometimes heard opponents of total abstinence ask, with a sneer, "Who ever made a fortune by what he saved by abstaining from drink?" Suppose we had each our favourite club or bar-parlour, in which we spent our evenings after our day's hard toil, what opportunities should we have had for discussing the affairs of the day, or of devising new work for the next? No, it is just here where the saving is effected — not merely of the cost of the drink, but of the golden opportunities of taking counsel together, and directing our efforts into one channel. This result was not obtained without the constant exercise of a spirit of ' brotherly condescension ' and mutual forbearance, and the bearing in mind of the old Cornish motto which furnishes the title for this volume,

"ONE AND ALL."

I will not attempt to draw a moral from the story of the birth of a great industry, which I have here set forth; for if the reader has not seen from the course of the narrative itself what may be accomplished, even under the most adverse circumstances, I shall have failed in my object in writing it. But for the encouragement of those who have not yet made the final start in their life's work, and before whom the horizon may seem sufficiently dark, I may add, that although all the five brothers originally composing the firm of "Tangyes" were put to employments they did not like, and which they left at the first opportunity, yet by the exercise of patience, determination, and self-control, combined with great industry, both in the conduct of the business, and in mastering the principles upon which its success depended, they were enabled to build up a concern which has given continuous employment to thousands of people for more than a quarter of a century.