Clifton Suspension Bridge

The Clifton Suspension Bridge spans the Avon Gorge, and linking Clifton in Bristol to Leigh Woods in North Somerset, England.

Bridge Road, Leigh Woods, Bristol, BS8 3PA. Clifton Suspension Bridge Website.

An excellent Visitor Centre was opened in 2015 on the south side of the bridge.

General

The idea of building a bridge across the Avon Gorge originated in 1753, with a bequest in the will of Bristolian merchant William Vick, who left £1,000 invested with instructions that when the interest had accumulated to £10,000, it should be used for the purpose of building a stone bridge between Clifton Down (which was in Gloucestershire, outside the City of Bristol, until the 1830s) and Leigh Woods (then in Somerset).

By 1829, Vick's bequest had reached £8,000, but it was estimated that a stone bridge would cost over ten times that amount. An Act of Parliament was passed to allow a wrought iron suspension bridge to be built instead, and tolls levied to recoup the cost.

A competition was held to find a design for the bridge; the judge, Thomas Telford, rejected all designs, and tried to insist on a design of his own, a suspension bridge supported on tall Gothic towers. Telford claimed that no suspension bridge could exceed the 600 feet span of his own Menai Bridge.

1831 A second competition, held with new judges, was won by the design of Isambard Kingdom Brunel on 16 March, for a suspension bridge with fashionably Egyptian-influenced towers.

An attempt to build Brunel's design in 1831 was stopped by the Bristol Riots, which severely dented commercial confidence in Bristol.

1836 Work was not started again until 1836, and thereafter the capital from Vick's bequest and subsequent investment proved woefully inadequate.

By 1843, the towers had been built in unfinished stone, but funds were exhausted.

In 1851, the ironwork was sold and used to build the Brunel-designed Royal Albert Bridge on the railway between Plymouth and Saltash.

Brunel died in 1859, without seeing the completion of the bridge. Brunel's colleagues in the Institution of Civil Engineers felt that completion of the Bridge would be a fitting memorial, and started to raise new funds.

In 1860, Brunel's Hungerford Suspension Bridge, over the Thames in London, was demolished to make way for a new railway bridge to Charing Cross railway station, and its chains were purchased for use at Clifton. A slightly revised design was made by William Henry Barlow and John Hawkshaw; it has a wider, higher and sturdier deck than Brunel intended, triple chains instead of double, and the towers were left as rough stone rather than being finished in Egyptian style.

Work on the bridge was restarted in 1862, and was complete by 1864.

Towers: Although similar in size, the bridge towers are by no means identical in design. Leigh (south) tower has chamfered corners. The Clifton tower has square corners, and has openings in the sides. The arches above the road have different shapes on the two towers. Brunel's original plan proposed the towers be topped with fashionable sphinxes, but the ornaments were never constructed.

Abutments: The 85 ft tall Leigh Woods tower stands atop a 110 ft red sandstone clad abutment. In 2002 it was discovered that this was not a solid structure but contained 12 vaulted chambers up to 35 ft high, linked by shafts and tunnels. It is now possible to visit two of these chambers on guided 'Hard Hat Tours'.

Saddles: Roller mounted "saddles" at the top of each tower allow movement of the chains when loads pass over the bridge. Though their total travel is miniscule, their ability to absorb forces created by chain deflection prevents damage to both tower and chain.

Chains, Hangers, and Deck: The bridge has three independent wrought iron chains per side, from which the bridge deck is suspended by eighty-one matching vertical wrought-iron rods ranging from 65 ft at the ends to 3 ft in the centre. Composed of numerous parallel rows of eyebars connected by bolts, the chains are anchored in tunnels in the rocks 60 ft below ground level at the sides of the gorge. The deck was originally laid with wooden planking, later covered with asphalt, which has been renewed in 2009.

The weight of the bridge, including chains, rods, girders and deck is approximately 1,500 tons.

The above information is largely drawn from Wikipedia[1]

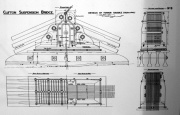

Saddles

The change in direction of the chains in passing over the top of the towers is accommodated by iron saddles which incorporate rollers. The rollers facilitate changes in catenary due to load or temperature changes, and also minimise the transmission of longitudinal forces form the chains to towers.

The main span chains and the anchor chains are connected, not directly to each other, but through the medium of 13 vertical iron plates, arranged ‘toast rack’ fashion - see drawing. The plates are sandwiched between a pair of 'stirrup'-shaped iron castings. The required gap between each plate (for the 12 chain links) is established by plate washers, the whole 'sandwich' being held together by six long bolts passing through the plates and the castings.

Each 'stirrup' casting has two feet which sit on a large cast iron plate. The plate can be seen in the drawing, distinguished by chamfered edges. The feet of the stirrup castings are bolted to this plate.

The chamfered plate sits on 50 rollers, and these in turn run on the planed surfaces of a rectangular iron plate. This plate is supported by four large fish-bellied cast iron beams, which bear the name Barrett, Exall and Andrewes. The beams are supported on the tower's masonry. The whole assembly is set at a slight angle to the horizontal, sloping down towards the 'land' side.

It is recorded that the saddles were previously used on the Hungerford Bridge in London. However, at Hungerford the chains on each side were two-high, compared with three-high at Clifton. We will now examine how the extra chain was accommodated at Clifton, and consider the extent to which old and new saddle components were used.

The extra chains were accommodated by adding an 'auxiliary saddle' on top of the Hungerford saddle. Specifically, this was a stack of 13 iron plates, bored for the two pins of the centre and main span chains. This stack sits on top of the original Hungerford stack, and is clamped together and united to the main stack by means of the pair of 'stirrup' castings. It therefore appears that the only new (1860s) parts are the auxiliary saddle components, the stirrup castings, and various fasteners.

It is reasonable to suppose that efforts were made to ensure that the bottom edges of the plates of the main (ex-Hungerford) 'toast rack' were all well-seated on the base casting. This was presumably achieved by temporarily bolting the stack of 13 plates together to bore the four holes and to plane the base of the plates. For the 'auxiliary saddle', the drawing implies that its plates are unsupported at the bottom, but it seems more likely that there is a plate inserted in the gap.

Several photographs of one of the saddles are available here[2]. One photo shows that one set of links is perforated by a rectangular slot, whose function is not clear.