James Nasmyth by James Nasmyth: Chapter 1

CHAPTER I. MY ANCESTRY.

Our history begins long before we are born. We represent the hereditary influences of our race, and our ancestors virtually live in us. The sentiment of ancestry seems to be inherent in human nature, especially in the more civilised races. At all events, we cannot help having a due regard for our forefathers. Our curiosity is stimulated by their immediate or indirect influence upon ourselves. It may be a generous enthusiasm, or, as some might say, a harmless vanity, to take pride in the honour of their name. The gifts of nature, however, are more valuable than those of fortune and no line of ancestry, however honourable, can absolve us from the duty of diligent application and perseverance, or from the practice of the virtues of self-control and self-help.

Sir Bernard Burke, in his Peerage and Baronetage, gives a faithful account of the ancestors from whom I am lineally descended. [1] "The family of Naesmyth," he says, "is one of remote antiquity in Tweeddale, and has possessed lands there since the 13th century." They fought in the wars of Bruce and Baliol, which ended in the independence of Scotland.

The following is the family legend of the origin of the name of Naesmyth:—

In the troublous times which prevailed in Scotland before the union of the Crowns, the feuds between the King and the Barons were almost constant. In the reign of James III. the House of Douglas was the most prominent and ambitious. The Earl not only resisted his liege lord, but entered into a combination with the King of England, from whom he received a pension. He was declared a rebel, and his estates were confiscated. He determined to resist the royal power, and crossed the Border with his followers. He was met by the Earl of Angus, the Maxwells, the Johnstons, and the Scotts. In one of the engagements which ensued the Douglases appeared to have gained the day, when an ancestor of the Naesmyths, who fought under the royal standard, took refuge in the smithy of a neighbouring village. The smith offered him protection, disguised him as a hammerman, with a leather apron in front, and asked him to lend a hand at his work.

While thus engaged a party of the Douglas partisans entered the smithy. They looked with suspicion on the disguised hammerman, who, in his agitation, struck a false blow with the sledge hammer, which broke the shaft in two. Upon this, one of the pursuers rushed at him, calling out, "Ye're nae smyth!" The stalwart hammerman turned upon his assailant, and, wrenching a dagger from him, speedily overpowered him. The smith himself, armed with a big hammer, effectually aided in overpowering and driving out the Douglas men. A party of the royal forces made their appearance, when Naesmyth rallied them, led them against the rebels, and converted what had been a temporary defeat into a victory. A grant of lands was bestowed upon him for his service. His armorial bearings consisted of a hand dexter with a dagger, between two broken hammer-shafts, and there they remain to this day. The motto was, ‘Non arte sed marte’, "Not by art but by war." In my time I have reversed the motto (Non marte sed arte); and instead of the broken hammer-shafts, I have adopted, not as my "arms" but as a device, the most potent form of mechanical art — the Steam Hammer.

Sir Michael Naesmyth, Chamberlain of the Archbishop of St. Andrews, obtained the lands of Posso and Glenarth in 1544, by right of his wife, Elizabeth, daughter and heiress of John Baird of Posso. The Bairds have ever been a loyal and gallant family. Sir Gilbert, father of John Baird, fell at Flodden in 1513, in defence of his king. The royal eyrie of Posso Crag is on the family estate and the Lure worn by Queen Mary, and presented by her son James VI. to James Naesmyth, the Royal Falconer, is still preserved as a family heirloom.

During the intestine troubles in Scotland, in the reign of Mary, Sir Michael Naesmyth espoused the cause of the unfortunate Queen. He fought under her banner at Langside in 1568. He was banished, and his estates were seized by the Regent Moray. But after the restoration of peace, the Naesmyths regained their property. Sir Michael died at an advanced age.

He had many sons. The eldest, James, married Joana, daughter of William Veitch or Le Veitch of Dawick. By this marriage the lands of Dawick came into the family. He predeceased his father, and was succeeded by his son James, the Royal Falconer above referred to. Sir Michael's second son, John, was chief chirurgeon to James VI. of Scotland, afterwards James I. of England, and to Henry, Prince of Wales. He died in London in 1613, and in his testament he leaves "his hert to his young master, the Prince's grace." Charles I., in his instructions to the President of the Court of Session, enjoins "that you take special notice of the children of John Naesmyth, so often recommended by our late dear father and us." Two of Sir Michael's other sons were killed at Edinburgh in 1588, in a deadly feud between the Scotts and the Naesmyths. In those days a sort of Corsican vendetta was carried on between families from one generation to another.

Sir Michael Naesmyth, son of the Royal Falconer, succeeded to the property. His eldest son James was appointed to serve in Claverhouse's troop of horse in 1684. Among the other notable members of the family was James Naesmyth, a very clever lawyer. He was supposed to be so deep that he was generally known as the "Deil o' Dawyk." His eldest son was long a member of Parliament for the county of Peebles; he was, besides, a famous botanist, having studied under Linnaeus. Among the inter-marriages of the family were those with the Bruces of Lethen, the Stewarts of Traquhair, the Murrays of Stanhope, the Pringles of Clifton, the Murrays of Philiphaugh, the Keiths (of the Earl Marischal's family), the Andersons of St. Germains, the Marjoribanks of Lees, and others.

In the fourteenth century a branch of the Naesmyths of Posso settled at Netherton, near Hamilton. They bought an estate and built a residence. The lands adjoined part of the Duke of Hamilton's estate, and the house was not far from the palace. There the Naesmyths remained until the reign of Charles II. The King, or his advisers, determined to introduce Episcopacy, or, as some thought, Roman Catholicism, into the country, and to enforce it at the point of the sword.

The Naesmyths had always been loyal until now. But to be cleft by sword and pricked by spear into a religion which they disbelieved, was utterly hateful to the Netherton Naesmyths. Being Presbyterians, they held to their own faith. They were prevented from using their churches, and they accordingly met on the moors, or in unfrequented places for worship. [2] The dissenting Presbyterians assumed the name of Covenanters. Hamilton was almost the centre of the movement. The Covenanters met, and the King's forces were ordered to disperse them. Hence the internecine war that followed. There were Naesmyths on both sides — Naesmyths for the King, and Naesmyths for the Covenant.

In an early engagement at Drumclog, the Covenanters were victorious. They beat back Claverhouse and his dragoons. A general rising took place in the West Country. About 6,000 men assembled at Hamilton, mostly raw and undisciplined countrymen. The King's forces assembled to meet them, - 10,000 well-disciplined troops, with a complete train of field artillery. What chance had the Covenanters against such a force? Nevertheless, they met at Bothwell Bridge, a few miles west of Hamilton.

It is unnecessary to describe the action. [3] The Covenanters, notwithstanding their inferior force, resisted the cannonade and musketry of the enemy with great courage. They defended the bridge until their ammunition failed. When the English Guards and the artillery crossed the bridge, the battle was lost. The Covenanters gave way, and fled in all directions; Claverhouse, burning with revenge for his defeat at Drumclog, made a terrible slaughter of the unresisting fugitives. One of my ancestors brought from the battlefield the remnant of the standard; a formidable musquet - "Gun Bothwell" we afterwards called it; an Andrea Ferrara; and a powder-horn. I still preserve these remnants of the civil war.

My ancestor was condemned to death in his absence, and his property at Netherton was confiscated. What became of him during the remainder of Charles II.'s reign, and the reign of that still greater tormentor, James II., I do not know. He was probably, like many others, wandering about from place to place, hiding "in wildernesses or caves, destitute, afflicted, and tormented." The arrival of William III. restored religious liberty to the country, and Scotland was again left in comparative peace.

My ancestor took refuge in Edinburgh, but he never recovered his property at Netherton. The Duke of Hamilton, one of the trimmers of the time, had long coveted the possession of the lands, as Ahab had coveted Naboth's vineyard. He took advantage of the conscription of the men engaged in the Bothwell Brig conflict, and had the lands forfeited in his favour. I remember my father telling me that, on one occasion when he visited the Duke of Hamilton in reference to some improvement of the grounds adjoining the palace, he pointed out to the Duke the ruined remains of the old residence of the Naesmyths. As the first French Revolution was then in full progress, when ideas of society and property seemed to have lost their bearings, the Duke good-humouredly observed, "Well, well, Naesmyth, there's no saying but what, some of these days, your ancestors' lands may come into your possession again!"

Before I quit the persecutions of "the good old times," I must refer to the burning of witches. One of my ancient kinswomen, Elspeth Naesmyth, who lived at Hamilton, was denounced as a witch. The chief evidence brought against her was that she kept four black cats, and read her Bible with two pairs of spectacles! a practice which shows that she possessed the spirit of an experimental philosopher. In doing this she adopted a mode of supplementing the power of spectacles in restoring the receding power of the eyes. She was in all respects scientifically correct. She increased the magnifying power of the glasses; a practice which is preferable to single glasses of the same power, and which I myself often follow. Notwithstanding this improved method of reading her Bible, and her four black cats, she was condemned to be burnt alive! She was about the last victim in Scotland to the disgraceful superstition of witchcraft.

The Naesmyths of Netherton having lost their ancestral property, had to begin the world again. They had to begin at the beginning. But they had plenty of pluck and energy. I go back to my great-great-grandfather, Michael Naesmyth, who was born in 1652. He occupied a house in the Grassmarket, Edinburgh, which was afterwards rebuilt, in 1696. His business was that of a builder and architect. His chief employment was in designing and erecting new mansions, principally for the landed gentry and nobility. Their old castellated houses or towers were found too dark and dreary for modern uses. The drawbridges were taken down, and the moats were filled up. Sometimes they built the new mansions as an addition to the old. But oftener they left the old castles to go to ruin; or, what was worse, they made use of the stone and other materials of the old romantic buildings for the construction of their new residences.

Michael Naesmyth acquired a high reputation for the substantiality of his work. His masonry was excellent, as well as his woodwork. The greater part of the latter was executed in his own workshops at the back of his house in the Grassmarket. His large yard was situated between the back of the house and the high wall that bounded the Greyfriars Churchyard, to the east of the flight of steps which forms the main approach to George Heriot's Hospital.

The last work that Michael Naesmyth was engaged in cost him his life. He had contracted with the Government to build a fort at Inversnaid, at the northern end of Loch Lomond. It was intended to guard the Lowlands, and keep Rob Roy and his caterans within the Highland Border. A Promise was given by the Government that during the progress of the work a suitable force of soldiers should he quartered close at hand to protect the builder and his workmen.

Notwithstanding many whispered warnings as to the danger of undertaking such a hazardous work, Michael Naesmyth and his men encamped upon the spot, though without the protection of the Government force. Having erected a temporary residence for their accommodation, he proceeded with the building of the fort. The work was well advanced by the end of 1703, although the Government had treated all Naesmyth's appeals for protection with evasion or contempt.

Winter set in with its usual force in those northern regions. One dark and snowy night, when Michael and his men had retired to rest, a loud knocking was heard at the door. "Who's there?" asked Michael. A man outside replied, "A benighted traveller overtaken by the storm." He proceeded to implore help, and begged for God's sake that he might have shelter for the night. Naesmyth, in the full belief that the traveller's tale was true, unbolted and unbarred the door, when in rushed Rob Roy and his desperate gang. The men, with the dirks of the Macgregors at their throats, begged hard for their lives. This was granted on condition that they should instantly depart, and take an oath that they should never venture within the Highland border again.

Michael Naesmyth and his men had no alternative but to submit, and they at once left the bothy with such scanty clothing as the Macgregors would permit them to carry away. They were marched under an armed escort through the snowstorm to the Highland border, and were there left with the murderous threat that, if they ever returned to the fort, certain death would meet them. [4]

Poor Michael never recovered from the cold which he caught during his forced retreat from Inversnaid. The effects of this, together with the loss and distress of mind which he experienced from the Government's refusal to pay for his work — notwithstanding their promise to protect him and his workmen from the Highland freebooters — so preyed upon his mind that he was never again able to devote himself to business. One evening, whilst sitting at his fireside with his grandchild on his knee, a death-like faintness came over him; he set the child down carefully by the side of his chair, and then fell forward dead on his own hearthstone.

Thus ended the life of Michael Naesmyth in 1705, at the age of fifty-three. He was buried by the side of his ancestors in the old family tomb in the Greyfriars Churchyard.

This old tomb, dated 1614, though much defaced, is one of the most remarkable of the many which surround the walls of that ancient and memorable burying-place. Greyfriars Churchyard is one of the most interesting places in Edinburgh. The National Covenant was signed there by the Protestant nobles and gentry of Scotland in 1638. The prisoners taken at the battle of Bothwell Brig were shut up there in 1679, and, after enduring great privations, a portion of the survivors were sent off to Barbadoes.

When I first saw the tombstone, an ash tree was growing out of the top of the main body of it, though that has since been removed. In growing, the roots had pushed out the centre stone, which has not been replaced. The tablet over it contains the arms of the family, the broken hammer-shafts, and the motto "Non arte sed marte." There are the remains of a very impressive figure, apparently rising from her cerements. The body and extremities remain, but the head has been broken away. There is also a remarkable motto on the tablet above the tombstone – “Ars mihi vim contra Fortunae;” which I take to be, “Art is my strength in contending against Fortune,” - a motto which is appropriate to my ancestors as well as to myself.

The business was afterwards carried on by Michael's son, my great-grandfather. He was twenty-seven years old at the time of his father's death, and lived to the age of seventy-three. He was a man of much ability and of large experience. One of his great advantages in carrying on his business was the support of a staff of able and trustworthy foremen and workmen. The times were very different then from what they are now. Masters and men lived together in mutual harmony. There was a kind of loyal family attachment among them, which extended through many generations. Workmen had neither the desire nor the means for shifting about from place to place. On the contrary, they settled down with their wives and families in houses of their own, close to the workshops of their employers. Work was found for them in the dull seasons when trade was slack, and in summer they sometimes removed to jobs at a distance from headquarters. Much of this feeling of attachment and loyalty between workmen and their employers has now expired. Men rapidly remove from place to place. Character is of little consequence. The mutual feeling of goodwill and zealous attention to work seems to have passed away. Sudden change, scamping, and shoddy have taken their place.

My grandfather, Michael Naesmyth, succeeded to the business in 1751. He more than maintained the reputation of his predecessors. The collection of first-class works on architecture which he possessed, such as the folio editions of Vitruvius and Palladio, which were at that time both rare and dear, showed the regard he had for impressing into his designs the best standards of taste. The buildings he designed and erected for the Scotch nobility and gentry were well arranged, carefully executed, and thoroughly substantial. He was also a large builder in Edinburgh. Amongst the houses he erected in the Old Town were the principal number of those in George Square. In one of these, No. 25, Sir Walter Scott spent his boyhood and youth. They still exist, and exhibit the care which he took in the elegance and substantiality of his works.

I remember my father pointing out to me the extreme care and attention with which he finished his buildings. He inserted small fragments of basalt into the mortar of the external joints of the stones, at close and regular distances, in order to protect the mortar from the adverse action of the weather. And to this day they give proof of their efficiency; the basalt protects the joints, and at the same time gives a neat and pleasing effect to what would otherwise have been the merely monotonous line of mason-work.

A great change was about to take place in the residences of the principal people of Edinburgh. The cry was for more light and more air. The extension of the city to the south and west was not sufficient. There was a great plateau of ground on the north side of the city, beyond the North Loch. But it was very difficult to reach; being alike steep on both sides of the Loch. At length, in 1767, an Act was obtained to extend the royalty of the city over the northern fields, and powers were obtained to erect a bridge to connect them with the Old Town.

The magistrates had the greatest difficulty in inducing the inhabitants to build dwellings on the northern side of the city. A premium was offered to the person who should build the first house; and £20 was awarded to Mr. John Young on account of a mansion erected by him close to George Street. Exemption from burghal taxes was also granted to a gentleman who built the first house in Princes Street. My grandfather built the first house in the southwest corner of St. Andrew Square, for the occupation of David Hume the historian, as well as the two most important houses in the centre of the north side of the same square. One of these last was occupied by the venerable Dr. Hamilton, a very conspicuous character in Edinburgh. He continued to wear the cocked hat, the powdered pigtail, tights, and large shoe buckles, for about sixty years after the costume had become obsolete. All these houses are still in perfect condition, after resisting the ordinary tear and wear of upwards of a hundred and ten northern winters. The opposition to building houses across the North Loch soon ceased; and the New Town arose, growing from day to day, until Edinburgh became one of the most handsome and picturesque cities in Europe.

There is one other thing that I must again refer to - namely, the highly-finished character of my grandfather's work. Nothing merely moderate would do. The work must be of the very best. He took special pride in the sound quality of the woodwork and its careful workmanship. He chose the best Dantzic timber because of its being of purer grain and freer from knots than other wood. In those days the lower part of the walls of the apartments were wainscoted — that is, covered by timber framed in large panels. They were from three to four feet wide, and from six to eight feet high. To fit these in properly required the most careful joiner-work. It was always a holiday treat to my father, when a boy, to be permitted to go down to Leith to see the ships discharge their cargoes of timber. My grandfather had a wood-yard at Leith, where the timber selected by him was piled up to be seasoned and shrunk, before being worked into its various appropriate uses. He was particularly careful in his selection of boards or stripes for floors, which must be perfectly level, so as to avoid the destruction of the carpets placed over them. The hanging of his doors was a matter that he took great pride in — so as to prevent any uneasy action in opening or closing. His own chamber doors were so well hung that they were capable of being opened and closed by the slight puff of a hand-bellows.

The excellence of my grandfather's workmanship was a thing that my own father always impressed upon me when a boy. It stimulated in me the desire to aim at excellence in everything that I undertook; and in all practical matters to arrive at the highest degree of good workmanship. I believe that these early lessons had a great influence upon my future career.

I have little to record of my grandmother. From all accounts, she was everything that a wife and mother should be. My father often referred to her as an example of the affection and love of a wife to her husband, and of a mother to her children. The only relic I possess of her handiwork is a sampler, dated 1743, the needlework of which is so delicate and neat, that to me it seems to excel everything of the kind that I have seen.

I am fain to think that her delicate manipulation in some respects descended to her grandchildren, as all of them have been more or less distinguished for the delicate use of their fingers — which has so much to do with the effective transmission of the artistic faculty into visible forms. The power of transmitting to paper or canvas the artistic conceptions of the brain through the fingers, and out at the end of the needle, the pencil, the pen, or brush, or even the modelling tool or chisel, is that which, in practical fact, constitutes the true artist.

This may appear a digression; though I cannot look at my grandmother's sampler without thinking that she had much to do with originating the Naesmyth love of the Fine Arts, and their hereditary adroitness in the practice of landscape and portrait painting, and other branches of the profession.

My grandfather died in 1803, at the age of eighty-four, and was buried by his father's side in the Naesmyth ancestral tomb in Greyfriars Churchyard. His wife, Mary Anderson, who died before him, was buried in the same place.

Michael Naesmyth left two sons — Michael and Alexander. The eldest was born in 1754. It was intended that he should have succeeded to the business and, indeed, as soon as he reached manhood he was his father's right-hand man. He was a skilful workman, especially in the finer parts of joiner-work. He was also an excellent accountant and bookkeeper. But having acquired a taste for reading books about voyages and travels, of which his father's library was well supplied, his mind became disturbed, and he determined to see something of the world. He was encouraged by one of his old companions, who had been to sea, and realised some substantial results by his voyages to foreign parts. Accordingly Michael, notwithstanding the earnest remonstrances of his father, accompanied his friend on the next occasion when he went to sea.

After several voyages to the West Indies and other parts of the world, which both gratified and stimulated his natural taste for adventures, and also proved financially successful, his trading ventures at last met with a sad reverse, and he resolved to abandon commerce, and enter the service of the Royal Navy. He was made purser, and in this position he entered into a new series of adventures. He was present at many naval engagements. But he lost neither life nor limb. At last he was pensioned, and became a resident at Greenwich Hospital. He furnished the rooms that were granted him with all manner of curiosities, which his roving naval life had enabled him to collect. His original skill as a worker in wood came to life again. The taste of the workman and the handiness of the seaman enabled him to furnish his rooms at the Hospital in a most quaint and amusing manner.

My father had a most affectionate regard for Michael, and always spent some days with him when he had occasion to visit London. One bright summer day they went to have a stroll together on Blackheath; and while my uncle was enjoying a nap on a grassy knoll, my father made a sketch of him, which I still preserve. Being of a most cheerful disposition, and having a great knack of detailing the incidents of his adventurous life, he became a great favourite with the resident officers of the Hospital and was always regarded by them as real good company. He ended his days there in peace and comfort, in 1819, at the age of sixty-four.

See Also

Foot Notes

- ↑ Sir B. Burke's Peerage and Baronetage. Ed. 1879. Pp. 885-6.

- ↑ In the reign of James II, of England and James VII. of Scotland a law was enacted, "that whoever should preach in a conventicle under a roof, or should attend, either as a preacher or as a hearer, a conventicle in the open air, should be punished with death and confiscation of property."

- ↑ See the account of a Covenanting Officer in the Appendix to the Scots Worthies. See also Sir Walter Scott's Old Mortality, where the battle of Bothwell Brig is described.

- ↑ Another attempt was made to build the fort at Inversnaid. But Rob Roy again surprised the small party of soldiers who were in charge. They were disarmed and sent about their business. Finally, the fort was rebuilt, and placed under command of Captain (afterwards General) Wolfe. When peace fell upon the Highlands and Rob Roy's country became the scene of picnics, the fort was abandoned and allowed to go to ruin.

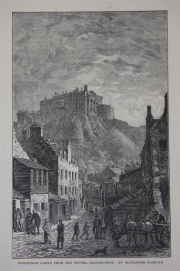

The lower house, at the right hand corner of the engraving, with the three projecting gable ends, is the house in question.