Engineers and Mechanics Encyclopedia 1839: Railways: Walter Hancock

Pursuing our narration chronologically, one must now draw the reader's attention to the labours of Walter Hancock, who commenced his career of constructing locomotive carriages about the same time as Goldsworthy Gurney; but whose mechanical arrangements possess far more originality and genuine merit, and have, in consequence, been attended with greater success.

It was at this period (1827) that Mr. Hancock took out his first patent, which was for a light high-pressure boiler, designed for locomotive purposes; the description of this we shall, however, defer, until we have made a retrospect of his previous labours.

This gentleman, we are informed, began his experiments in the year 1824, with an engine of his own invention, and of a very singular construction; but which he imagined was peculiarly suitable for locomotive purposes. The engine had neither cylinder nor piston, but consisted of two flexible bags, made of his brother's patent artificial leather, composed of caoutchouc, combined with several layers of linen. Communications, by means of a four-way cock, admitted the steam alternately into these bags, which being attached to a suitable frame with a slide motion, the alternate filling and exhausting took place, and the reciprocation produced by their expansion and contraction was communicated to a crank, which converted it into circular motion.

The caoutchouc was found to answer for a short tins; but the heat soon rendered the bags permeable, and of course the engine useless. Having satisfied his mind that caoutchouc could not be efficaciously employed in this way, he resorted to cylinders of the ordinary metallic kind, and in a short time had completed a model therewith of a steam-carriage, which was tried on the public road. The indications of success which this model gave, decidedly convinced him of the feasibility of the project of steam propulsion on the common road, and that the principal thing required, was a compact, light, and powerful boiler, which he next set about to contrive.

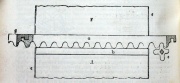

The difficulties which had been experienced by various individuals in the construction of tubular boilers, led Mr. Hancock to consider of some arrangement by which the water, exposed to the action of the fire, might be less divided, and yet extended over a large surface; and the plan now occurred to him, which he has since successfully followed in the several steam-carriages he has built, and has applied to other purposes. In the annexed figure is represented an elevation of the first modification of this boiler, with a part of the casing removed to show the interior structure.

At B is the fire-place; D the stoke-hole; E-E are a series of flat parallel chambers to hold the water, made of the toughest sheet-iron, and placed side by side, at a sufficient distance apart for the flames and heated air to pass up between them, as shown at H-H. Each of these flat vessels extends across the furnace chamber, so as to fill its whole area in a vertical plane; and they are all connected at the bottom, for keeping the water in each at a uniform level; and at the top of each of the chambers there is a steam-pipe that leads into another larger steam-pipe, common to them all, and by which the engines are supplied.

To keep the individual water chambers E-E at uniform distances apart, and confer, at the same time, adequate strength to them, a series of vertical bars or fillets are fixed between each pair. Therefore, instead of the flames ascending between each pair of plates in one unbroken sheet, it is subdivided, and made to pass through a number of rectangular channels, representing in their outline so many square tubes. This combination of water chambers and alternate flues, is bound together by a system of very massive bolts externally, proved to be capable of sustaining a vastly greater pressure than the boiler is ever subjected to; and it is unquestionably a great merit in this boiler, that the thinness of metal, and consequent weakness of the individual water chambers, constitutes each, in effect, a safety valve.

A better arrangement than this for absorbing the heat of the furnace, and, consequently, for the rapid production of steam, seems scarcely to have been requisite; but the active mind of the inventor, ever bent upon improvement, soon found means to increase its efficiency, and reduce its weight; which are, of course, objects of the utmost importance in steam locomotion.

The increased efficiency was obtained by "embossing" the plates; by punching or pressing them between dies, so as to cause a series of hemispherical bosses, of nearly the shape and size of watch-glasses, to be projected all over their external surfaces; so that when the chambers are brought together, the tops of these come into contact, and thus a series of spaces are formed between them, as shown at h-h-h in the second cut; e-e being the water chambers, the projections on which are sufficiently obvious; the surface of metal covered with water is thus greatly extended, and the ascending current of heated matters is made to impinge against their projections, which are not placed in vertical lines upwards, but zig-zag, as shown in the following cut, which represents a side view of a portion of one of the chambers.

The vertical bars, described in the first modification, are therefore here entirely got rid of, and their entire weight; and, at the same time, a much more powerful boiler obtained; and one that it is scarcely possible to exceed in compactness, which is a property of considerable importance in locomotion: and in tile facility of repair, which it admits of, it excels all others; there being nothing more to do than to unscrew the great internal bolts, take out the faulty chamber, and replace it by a new one, reconnecting the steam and water pipes, and screwing up the great bolts again. It remarkable circumstance, that Dr. Lardner condemns this boiler of Mr. Hancock's on the very grounds that we think its merit consists; which we shall here briefly state, in order that his opinion may have its due weight with our readers.

In his Treatise on the Steam Engine the Doctor observes, with respect to this invention, that "thin plates are the form which, mechanically considered, are unfavourable to strength." The inferences to be drawn from this remark are, that the plates have no support at their sides, and that Mr. Hancock was so weak minded as to depend for strength in a high-pressure boiler upon thin plate-iron; both of which inferences are obviously absurd and untrue. (Were we disposed to be hypercritical, we should say that the learned Doctor's position is, in every view, untenable - for we conceive that thin sheet-iron is, "mechanically considered," stronger than thick sheet-iron, having acquired by the rolling mills more tenacity and ductility.) The advantages of the thin metal above thick in Mr. Hancock's boiler, are evidently these; that every one of the compartments between the supports is not only in effect a perfect safety-valve, as before observed, but a much more rapid conductor of the heat to the water, than if it were formed of thick metal.

The next objection taken by Dr. Lardner is that the upper parts of the water chambers are liable to early destruction from containing no water. On this point we would individually merely observe that these parts are so far removed from the intense action of the fire, as not to be liable to early injury from that cause, and that the advantage of increasing the elasticity of the steam by the waste heat before it enters the chimney, more than compensates for the slightly increased oxidation that the metal may sustain from the heated air.

Dr. Lardner, however, so far from admitting that there is any advantage in heating the steam, insists that there is a positive loss; these are his words:- "It has been observed by engineers, and usually shown by experiment, that if steam be heated on the surface of the water, it will be decomposed, and its elasticity destroyed." Where can that engineer be found, and where may that experiment be seen? We venture to assert that the former has no name, and the latter no place. We need not stop to discuss this point, as our scientific readers well know that the statement is directly at variance with all reason and theory; and we know from experience, that it is equally at variance with practice. We have repeatedly applied a lighted brand to the steam chamber of a tubular boiler when the engine to which it was attached was working sluggishly, and the result has uniformly been, such a sudden accession of force as to cause the engine to go off with impetuous violence.

It was once a prevalent opinion, that the reheating of steam, so as to raise its temperature to the same degree as it would have acquired by heating the water alone, would have the effect of communicating to it a similar degree of elasticity; but those who tried it, being disappointed by finding the reality fall so far short of their high expectations, it was entirely overlooked by them; hence the unreflecting ran into the opposite extreme, some saying there was no advantage, and others that there was a loss; a loss of elasticity by the interposition of caloric!

We shall, however, close our remarks on this point by reference to the opinion of John Farey, who requires no additions to his name to distinguish him as the highest authority in this country on such subjects as the present. In his evidence before the Select Committee of the House of Commons on steam carriages, at page 42, he says,-

"Mr. Hancock has taken the middle course in subdividing the water in his boiler, having all that can be required for safety; and the weight, on the whole, I believe to be less than that of any other boiler which will produce the same power of steam; for, owing to the freedom with which the steam can get away in bubbles from the water, without carrying the water with it, the surface of the heated metal is never left without water. Hence a greater effect of boiling is attained from a given surface of metal and body of contained water, and that with a much greater durability of the metal plates, than I think will ever be obtained with small tubes."

Mr. Hancock being satisfied that he had obtained in this boiler the requisite means of generating adequate power, turned his attention to the various arrangements of the carriage and propelling machinery. His first carriage was constructed upon three wheels, and the power was applied through the medium of two vibrating engines fixed upon the crank axle of the fore wheel. The direct application of the power to the crank by this method, gave him ardent hopes of success; and three wheels have the unquestionable advantage of greater facility in steering. After many trials, however, and various alterations, experience proved that it was attended with so many "practical drawbacks," that it was finally abandoned.

After this, Mr. Hancock devoted much time to the construction of a propelling apparatus, under the idea that was so pertinaciously inculcated by writers (in spite of the experience to the contrary by railway engineers) that "the bite" of plain wheels upon the common road was insufficient to propel; but experience proved to him also, the utter uselessness of any such adjuncts as propellers, as they were distinctively termed; and he moreover found, in his first carriage, that the single fore wheel alone was fully adequate to perform that office.

Defective as this first carriage must necessarily have been, Mr. Hancock states in a memoir that he has had the kindness to transmit to us, that it ran many hundred miles in experimental trips from the writer's manufactory at Stratford, sometimes to Epping Forest, at others to Paddington, and frequently to Whitechapel. On one occasion it ran to Hounslow, and on another to Croydon. In every instance it accomplished the task assigned to it, and returned to Stratford on the same day on which it set out. Some of the experiments we personally witnessed.

Subsequently, this carriage went from Stratford, through Pentonville, to Turnham Green, over Hammersmith Bridge, and thence to Fulham. In that neighbourhood it remained several days, and made a number of excursions in different directions, for the gratification of some of the writer's friends, and others who had expressed a desire to witness its performance.

In the course of these early experimental trips, Mr. Hancock experienced the usual fate of all who run counter to long standing usages and prejudices; namely, to be ridiculed by the many, encouraged by but a very few, and fiercely opposed by all whose personal interests were threatened with injury by his proceedings. Some would admit frankly that the carriage worked well; but expressed their decided conviction that it would never answer for a continuance. Others would depreciate its performances, exaggerate its defects, and exult, as it were, in every instance of accidental stoppage.

If requiring temporary accommodation, through the failure of some part of the machinery, a circumstance naturally enough of frequent occurrence in this early period of his locomotive career, Mr. Hancock usually experienced the reverse of kind or considerate treatment. Exorbitant charges were made for the most trifling services, and important facilities withheld, which it would have cost nothing to afford. If temporarily detained on the road from the want of water, or from any other cause, he was assailed with hooting, yelling, hissing, and sometimes even with the grossest abuse; waggons, carts, coaches, vans, trucks, horsemen, and pedestrians, pressed so close on the carriage, as sometimes to preclude the possibility of moving; and his situation was often rendered very irksome and irritating; sometimes very hazardous. Undismayed by these untoward circumstances, however, he persevered in his experiments; and as the novelty of such exhibitions wore off, so did the excitement and the opposition which they at first produced.

Becoming convinced from experience that there was a disadvantage in applying the power directly to the crank, as before noticed, Mr. Hancock next placed the engines quite behind, and at the same time altered the form of the carriage, so as to make it more nearly resemble an ordinary horse carriage. Much study and labour were spent upon the various alterations that were suggested and tried from time to time. But the difficulty of keeping the machinery clean, owing to its proximity to the fire-place, as well as to the road, was found in practice to be so strong an objection, that this form of carriage was also abandoned. Nevertheless with this carriage, one point, of the greatest importance in steam travelling, was most satisfactorily determined.

The possibility of a steam carriage ascending steep hills had been doubted and questioned by many; and to remove, if possible, all scepticism on the subject, a day was appointed for taking his carriage up Pentonville-hill, which had a rise of 1 in 18 to 20, and a numerous party assembled to witness the experiment. A severe frost succeeding a shower of sleet, had completely glazed the road, so that horses could scarcely keep their footing. The carriage, however, without the aid of propellers, or any other such appendage, ascended the hill at considerable speed, and its summit was attained, while his competitors, with their horses, were yet but a little way from the bottom.

Stimulated by the success of such experiments, he remodelled the entire arrangement of the machinery. The trunnion engines were laid aside, and fixed ones substituted; and such other alterations and improvements adopted, as had suggested themselves during actual work upon the road. The carriage, as thus reconstructed, was called, in reference to the infancy of the undertaking, the "Infant." In this engine, the bulk of the machinery is fixed in the rear of the part appropriated to the passengers. There is, first, the boiler, with the fire-place under it. Second, a space between the boiler and passengers, for the engines, and the engineer who accompanies the carriage, whence he has the whole of the machinery within his reach, and open to his view; and is thus enabled, during the progress of the carriage, to lubricate the parts requiring oil - attend to the gauge-cocks, and regulate the supply of water to the boiler, as well as the degree of blast from the blower - to increase or diminish the generation of steam, according to the various states of tire road, and the wants of the engines, and generally to give his immediate attention to any portion of the machinery requiring adjustment. And, third, a pair of inverted fixed engines, working vertically on a crank shaft. The whole is on one framing, supported by four common coach springs, on the axle of each wheel.

On the crank shaft and on the axle of the hind wheels, are fixed indented pulleys, around which an endless chain passes, which communicates the power and rotary motion of the crank shaft to the hind axle, and propelling wheels, and thereby effects the progressive motion of the whole carriage.

When it is desired to back the carriage, the action of the engines is merely reversed, which can be effected almost instantly.

The advantages realised by the improved arrangement shown in the Infant are numerous. The engines are completely protected from the dirt and dust of the roads; are at all times in sight of the engineer, and every part of them is within his reach. The passengers, engines, boiler, fire-place, &c., are all equally relieved from concussion, by complete suspension on springs, similar to a stage coach; the chains allowing full play to the springs, and a vibrating stay from the crank to the axle preventing the pull of the chains, and securing a uniform distance between the axle and crank shaft.

By the employment, too, of a distinct crank shaft, the axletree, which has to carry all the weight, is not only preserved straight, and consequently of the best form to sustain that weight, but it is also relieved from the strain which it has to bear, where it forms both crank and axle, and has to propel the carriage, and carry the weight as well. The Infant thus fitted up, was tried in every possible way, during several months, and proved so perfectly efficient, that in all the carriages which Mr. Hancock has since constructed, he has adhered to the same general plan of arrangement, with the exception of some modifications in the details, which more extended experience has suggested.

But though the general arrangement of the Infant was such as to leave but little occasion for alteration, there were yet several important points that remained to be cleared up, such as the best proportions and size for the chambers of the boiler - the best form for each separate portion of the machinery - the proper position, size, and strength of the various parts, and also the most suitable kind of materials, so as to avoid as much as possible superfluous weight. Experiments to ascertain these various points occupied Mr. Hancock till the beginning of the year 1831, so that full six years had elapsed from the commencement of his locomotive pursuits, before the Infant was produced in a state somewhat to the satisfaction of his own mind.

The trials made during this probationary period, comprise a total of many hundred miles, all made upon the high roads, near London, principally in the vicinity of Stratford; between which place and Whitechapel, vehicles of every description being in constant motion, afforded him an excellent opportunity of obtaining practical experience, under every circumstance of difficulty, in which a steam-carriage might be expected to be placed; and this consideration determined him to give the most frequented road the preference.

In February, 1831, he commenced running the Infant regularly for hire, on the road between Stratford and London; not, certainly, with an anticipation of profit, but as a means of dissipating any remaining prejudices, and establishing a favourable judgment in the public mind as to the practicability of steam travelling on common roads. Mr. Hancock observes that it is an undeniable fact, and a source of proud satisfaction to him, that a steam carriage of his construction was the first that ever plied for hire on a common road, and that he achieved this triumph single-handed.

In the engraving is exhibited a sketch of the arrangement of the machinery of the Infant; the body of the carriage for the passengers being, however, fashioned more like an omnibus, as has been subsequently adopted by the patentee.

The description of this machine is thus given by Alexander Gordon, who has made many experimental trips in it: a is the fire-place, the fuel being laid upon the bars which are seen between the fire-place and the ash-pit b; the ash-pit is made air-tight, or nearly so, in order that the blast from the revolving fanners in g may be urged upwards through the fire. The fire-place is also necessarily kept close; it is provided with eye-holes, through which the fireman (who sits on a small seat behind the boiler) can view the state of the fire.

Fresh supplies of coke are dropped through the feeding hopper q. On this appendage are placed double doors, one of them being always shut, to prevent the blast escaping up the feeding hopper, when the coke is added to the fire. Steam is supplied to the engines d, of which there are two, through r, and the quantity is regulated by a valve at s, placed under the control of the guide, by means of a lever rod. The alternating vertical motion of the pistons in the engine cylinders is changed from the parallel motion t to the continuous circular motion of the cranks upon e, by the connecting-rod v.

Only one cylinder and its connexions can be shown in this "section." Two shives, or sprocket-wheels, arc placed upon the crank shaft e, and two also upon the axle f. An endless pitch chain passes round each pair of skives, and conveys the motion from e to f, and from thence to the hinder wheels.

It is necessary to keep the centre of e and the centre of f always parallel to, and equidistant from, each other, in order that the pitch chains may be in an equal state of tension: this is managed by means of two rods, one on each side of the carriage; the rods vibrate upon f as a centre, and cause the crank axis e, when the carriage is jolted, to describe a larger or smaller segment, with the same radices, as the body in which the engines are placed, plays up or down upon the springs. By this means concussions which affect the wheels, do not distress the machinery.

The radius rods are constantly vibrating, but the steam engine is securely and perfectly suspended upon flexible steel springs. Passengers are seated above the water tanks h-h; k is a connecting rod, by which the guide (at 1) can open or shut the throttle-valve s, and supply himself with what steam he requires, or shut it altogether off when stopping.

The whole engines, crank-shaft, and two throws, together with the pumps, are supported by flexible springs, which provide for any concussion on rough roads. The wheels turn loose on the axle, and one or other, or both, are fixed by a clutch when required. This clutch is on the outside of the wheel, and can be screwed out or in, as the case demands, with great facility. The turning of the carriage round to the off side is prepared for, by throwing out the offside clutch, and keeping in the near one and the turn round to the near side is prepared for, by throwing out the near clutch, and throwing in the off-side clutch. A little play is left between the catches in each clutch, so that a winding road may not oblige either wheel to be disengaged; and it is only in a short turn, or a turn round, that the clutch must be shifted, and this can be done in a very small space of time.

The fire is urged by the blower g, which is driven by a connexion with the engines. The waste steam is blown from the engines into the chimney, and so destroyed. The passengers are carried on the same machine, Mr. Hancock preferring that disposal of the weight to the dragging of it in a carriage behind.

The wheels of this carriage are a beautiful exhibition of strength and lightness combined. The spokes are all wedge-shaped, and where they are fastened into the nave, abut against each other. Their escape laterally is prevented by a large iron disc, at each end of the nave; and these being bolted through, confine the spokes very securely in their place.

Every eight miles he takes in water and coke; about seven cwt. of water, and sometimes eight: it depending upon the state of the roads, consuming most steam when the roads run heavy. The average time is about twenty minutes in getting up the steam, and he does not consume more than a bushel of coke for this purpose at first starting. The fore part of the vehicle is for passengers, so that all the machinery is quite behind the carriage; and the fore part of the carriage is entirely for the convenience of passengers, being made of greater or less length according to the number of persons.

The guide sits in front, at 1, and steers by means of a wheel, o, placed horizontally, as in Mr. Gurney's carriage; with this difference, that instead of the vertical spindle having a pinion at p, it is made with a horizontal drum or shive, upon which the middle of a chain is fastened; the ends of the chain are attached to the different ends of the fore-axletree in such manner that one or other of the fore-wheels may be hassled forward to turn the carriage.

One important improvement in the guide-motion has been made by Mr. Hancock, which is by means of a friction-strap or band at p, passed round a small friction drum; the guide can, by pressing a pedal with his foot, tighten this band on the drum when the carriage does not require to be turned out of the straight course. When the carriage is thus held in its line of direction, the guide's hands may be released from the tiller-wheel, o; for the jolting of the wheels over rough pavement or other inequalities of a road, are not sufficient to slip the friction-band. In case of requiring to turn, the guide's foot is either relaxed or taken off the pedal, and the tiller, o, worked by his hands. This band is of great importance its many cases, and by it a guide with feeble arms may steer as well as a Hercules.

This carriage is capable of carrying sixteen passengers, besides the engineer and guide. The weight of it, inclusive, of engines, boilers, coke, and water. but exclusive of attendants and passengers, is about three and a half tons.

The wheel tires are 3.5 inches wide. The diameter of hind wheels, 4 feet. The width of tire is not considered by the patentee to be so objectionable in practice as it might be considered. This he accounts for, by the variable nature of the roads; "a broad wheel on gravel is considered to be an advantage; it is however a great disadvantage on a road between wet and dry; but in those latter cases we have always an overplus of power (steam) blowing off at the safety-valve." Blowing off steam, either from the safety-valve or from the engines, creates no nuisance, because it is injected "into the fire in every direction," and so destroyed. The carriage can be turned in little more than ten feet, and stopped in much shorter space than any horse-coach. A metallic band, pressing upon the outer part of the wheel, is applied as a drag or brake when descending hills.

In slippery roads, or steep hills, both hind wheels are connected with the engine, in order to increase the adhesion to the road; but in general one driving wheel is found to be sufficient.

"In October, 1832, Mr. Hancock determined to make a trip to Brighton. On Wednesday, October 31, this steam carriage came from Stratford, through the streets of the city, at the different speeds necessary to keep its place behind or before other carriages as occasion required, and took up its quarters on Blackfriars Road, to prepare for the following day's trial. Accompanied by it scientific friend, a distinguished officer its the navy, I joined Mr. Hancock's friends on the next morning, making eleven passengers its all: We started at the rate of nine miles an hour, and kept this speed until we arrived at Redhill, (where all the coaches at this season require six horses,) which we ascended at the speed of between five and six miles an hour. The bane of the journey was an insufficient supply of coke and water; the water, indeed, we were obliged to suck up with one of Hancock's flexible hose pipes, at such ponds and streams as we could find. These difficulties delayed the completion of the journey (subsequently performed by steam in less than five hours) till next day; but on our return our speed was much increased, and one mile was accomplished up hill, at the speed of seventeen miles per hour."—Elemental Locomotion, p. 111.

"Reverting to the history of my carriages," observes Mr. Hancock, "I may remark that the Infant was the first steam carriage that ran on a common road for hire, which it commenced in February, 1831, between Stratford and London, and on which duty it continued several weeks in regular performance; but as I had not at this early period practised any person in steering, and my presence being required at home, I was under the necessity of taking it off the road. This carriage was also the first one that steamed through the public streets of the city of London.

“My time was now engaged in building a powerful carriage, the Era, which has only worked on proof on the roads in the neighbourhood, and been once Windsor, in 1832, the parties for whom it was built not having yet come to any determination upon it.

"A steam carriage company, ‘The London and Paddington,’ being now formed, I entered into agreement to build three carriages for them; the first of which, to have been titled the Demonstration, afterwards altered to Enterprise, was put to work between the City and Paddington, in April, 1833. It ran for sixteen succeeding days, and performed more than was stipulated for; but some disagreement led to the dissolution of this company, and the Enterprise became mine again by purchase, on the company winding up its affairs, which was nearly two years after the carriage was delivered to them; during all which time it stood in an open yard, belonging to the company's engineer, serving the office of a model for him to build another carriage by.”

These untoward circumstances, however, only served to renew the energies of Mr. Hancock, who busied himself in completing a new carriage for his own use, which he significantly denominated the Autopsy; it was brought upon the road in the same year (1833), and commenced running for hire between the city and Islington, in October, which it continued till the end of November. An engraved representation of this carriage is given; but as it may be remarked that the introduction, in this place, of a carriage built in 1838, does not accord with our intended chronological arrangement, it is proper we should explain, that this carriage contains nothing essentially different from the Infant, and that it can only be regarded as a second and more splendid edition of that carriage. All Mr. Hancock's subsequent carriages are built upon the same model in an engineering point of view; therefore, to keep the history of Mr. Hancock's locomotive career in a connected state, we shall here insert his brief account of all his carriages.

"During the winter I built the Era (now the Erin). This carriage commenced running for hire on the Paddington road, in August, 1834, on which duty it continued daily in company with the Autopsy, for upwards of three months, when I took them off in order to repaint and embellish the Era with appropriate devices, and alter its title to Erin, ready to fulfil an invitation that I had received from some gentlemen at Dublin, who were desirous of seeing its performances in their city.

“In the summer of this year (1834) I built a drag for a gentleman at Vienna, for which place it was shipped in July, after having stood satisfactory tests by taking it on different roads, with a loaded carriage attached.

"At the latter end of December I shipped the Erin for Dublin, and run it there, and in the vicinities, during the greatest part of January, 1835, much to the gratification of the inhabitants, it being the first that had run in that country.

"In 1835 I built a drag, by order, for Dublin, which has given most satisfactory proof of its power and efficiency, but which is still upon my hands.

"During the year 1835 I also brought out a gig calculated for the accommodation of three persons. I have run it repeatedly, and it is not to be believed by any but those who have travelled by it, how easy the motion of it is; I do not know the limit of its speed; probably from 27 to 30 miles, but it is seldom worked more than 17 or 18 miles per hour.

"In May this year (1836) I again put the carriages upon the Stratford and Paddington roads, and they have continued running daily for hire up to the present time (October) with all the precision and success that could be desired.

"In the month of July this year, a new and powerful carriage, the Automaton, was brought out, and has taken its share of work on the Paddington road, performing with the Infant in fine weather, these being both open carriages, whilst the Erin and Enterprise have run in wet weather.

"To avoid confusion in my narrative, I have not noticed in the order of time, many journeys which the carriages have performed; I might name amongst others, that the Infant, in the autumn of 1832, ran to Brighton, the first steam carriage that had been seen there; again it ran there in the summer of 1833, as did also the Autopsy. The first day the Automaton was worked, it took a party to Romford and back, without the smallest repair or alteration being required; the speed was from 10 to 12 miles per hour; this carriage has, within the last fortnight, run twice to Epping, each time with a party desirous of witnessing its performance on that hilly road; it travelled on the ordinary road at 12 to 14 miles, and ascended the hills, which are very steep, at 7 or 8 miles per hour." (We annex a representation of the Automaton, extracted from the Mechanics' Magazine.)

"The carriages have all proved more powerful than I had expected; the first time I was forcibly acquainted with this fact was whilst running for hire in the year 1834. A trifling casualty to the machinery of the Autopsy brought it to a stand, and the Erin was fetched to its assistance, when it towed the Autopsy up Pentonville-hill to the station in the City-road, without any material diminution of its speed, although this, as well as the other carriages, had only been calculated to carry a certain number of passengers, with water and fuel for the trip. The average working speed of all the carriages is from 10 to 12 miles an hour, though they may be pushed far beyond this. The fuel costs about two-pence-halfpenny a mile. The wear and tear is principally confined to the boilers, fireplaces, and wheels; but this is not so great as might be expected; and some of the carriages now running have had their boilers in use upwards of two years; when they are worn out it is only the chambers that require renewing, for tiny boilers are so constructed that all the main and expensive parts, such as bolts, stays, &c., will last for many years, and wear out several sets of chambers. As to the machinery, the wear and tear appears to be very trifling, as far as the carriages have yet performed; they have, in many respects, actually improved and even the Infant, which has been so many years in action, is in as good condition as ever it was in the original parts of its machinery.

"It may be readily supposed, that in bringing out a novelty of the kind now under consideration, and putting it into actual and effective operation, we have not been without accidents in our career, but are happy to say they have been few, and of trivial amount, with the exception of one, which was that of a workman, who, by a daring of the most imprudent stamp, caused an accident, which, whilst it proved the general safety of my boiler, I regret to say, deprived him of life. This statement was fully borne out to the satisfaction of the coroner and jury.

"I will now describe the general arrangement of my carriages.

"At the front sits the steersman, who governs the way and speed of the carriage; behind him is the body or open seats of the carriage, whichever may be its build; at the back of the body, and with a good screen or partition between it and the passengers, is the engine room, containing a pair of inverted engines, working direct upon the crank shaft, from which motion is communicated to the axle of the hind or working wheels, by endless chains and pulleys; adjoining the engine room, in the rear, is the boiler, with the fireplace under it. A lad stands behind to feed the fire as the carriage proceeds; and a man competent to judge of the working of the engines and machinery, and also to keep them oiled, is always in the engine room, whilst the carriage is working. The coke is contained in iron boxes at the back of the boiler, and the water for supplying the boiler is contained in tanks under the seats of the carriage. The fire is urged by a revolving blower under the flooring or body of the carriage.

"In conclusion, I will give a list of the carriages I have built, with the number of passengers they are each calculated to accommodate; not what they will and actually have carried, for this has sometimes, on particular occasions, been an increase of 50 per cent.; as an instance, the Autopsy, when first running to Islington, in 1833, carried, on two or three trips, 21 or 22 passengers, though its complement is but 12.

In 1833 Mr. Hancock took out a patent for improvements in the construction of furnaces to boilers, which will be found described in its proper place.

At page 128 we alluded to an improvement made by Mr. Hancock, in the furnaces of boilers, which was patented by him on the 15th January, 1833; the object of which is to remedy the inconvenience experienced by the formation and adhesion of clinkers upon the fire-bars, by which the combustion of the fuel is checked, and, consequently, the production of the steam, as well as the velocity of the carriage, considerably lessened.

By the present contrivance, Mr. Hancock draws out the foul floor of bars, and replaces them by a clean set, which operation, he states, is performed in much less time than is required to imperfectly clear by the rake.

In the figure, F represents the space occupied for the fire-place, in a vertical plane, and A is the ash-pit. a is a floor of bars, in one casting, and in their position for use; the outer bars on each side are cast with teeth underneath, forming racks; and there is a fixed rail under each rack, one of which is seen at b: these support the racks, and, consequently, the whole floor of bars, which are removed by turning the spindle of the pinion c, of which there are two, one at each end of the spindle, so as to operate upon both sides of the grating at once.

When a floor of bars has become foul, a clean floor is attached to it, as partly shown by the hooked joint at g, by which, as the foul floor is drawn out, the clean one is drawn in.

See Also

Sources of Information